Krenak

- Self-denomination

- Borum

- Where they are How many

- MG, MT, SP 494 (Siasi/Sesai, 2020)

- Linguistic family

- Krenák

Victims of several massacres – declared “Just Wars” by the Portuguese Colonial government –, the Krenak are the last remnants of the Botocudo do Leste (Eastern Botocudo). Today they live in a very small area, which they were able to recover with great difficulty.

Name and language

The Krenak or Borun are the last of the Botocudo do Leste (Eastern Botocudo), name given by the Portuguese in the end of the 18th Century to the groups that wore plugs in the ears and lips. They are also known as Aimoré, the name given to them by the Tupi, and as Grén or Krén, their self-denomination. Krenak comes from the name of the leader of the group that presided over the separation from the Gutkrák of the Pancas River, in the State of Espírito Santo, which occurred in the beginning of the 20th Century. It was at that time that they settled on the east bank of the Doce River, in the State of Minas Gerais, between the towns of Resplendor and Conselheiro Pena, where they still live, in a 4,000-hectare reservation. The Krenak Indigenous Post was created by the Serviço Nacional do Índio (National Service for the Indian, the first official organ for Indian policy) – SPI –, which, in the end of the 1920s, moved to it other Doce River Botocudo groups: Pojixá, Nakre-ehé, Miñajirum, Jiporók and Gutkrák, the latter the group the Krenak had previously separated from.

The Krenak belong to the linguistic group Macro-Jê, and speak a language called Borun. Only the women older than 40 are bilingual; men and young people and children of both sexes are Portuguese-speakers. In the past years the Krenak have been making an effort to have their children speak Borun.

Religion

At the time of contact, the Krenak were predominantly semi-nomadic hunters and gatherers, and their social organization was characterized by the constant fractioning of the group and by the labor division established along sex and age lines. Their religious system was centered in the figures of the Marét and on the enchanted spirits of their dead, the Nanitiong, who were responsible for the fecundation of the women and for announcing deaths. The Marét, who inhabit superior levels, were the great organizers of natural phenomena; among them, the most important was the Marét-khamaknian, the hero who created Man and the World, a benevolent being who was the civilizer of mankind.

Other entities of the Botocudo religious pantheon were the spirits of nature – the Tokón. They were responsible for choosing their intermediaries on Earth, the shamans, with whom they had contact during the rituals and who, almost always, were the political leaders of the group as well. There were also the souls, spirits that inhabited the bodies of humans and were acquired usually when the child turned 4-years old and had the first lip and ear plugs placed. The main soul left the body during sleep, and when it got lost the person became ill; before a person died, his/her main soul died inside the body. The other six souls that inhabited the body followed the corpse to the tomb, crying while floating above it. They were invisible to the community members present in the burial ceremony. If their needs for nourishment and light were not met, these complementary souls could become jaguars and threaten the village, because, if they did not eat, they would starve to death. A few years after the person’s death, good spirits would come from the superior level to take them to their space, from which they would not come back. From the bones of the dead there appeared spirits that would live in the underworld, which is where the sun shines while it’s dark on the Earth. These were large, evil, black spirits that wandered in the village attacking the living, especially the women, digging up the dead, frightening everyone by hitting hard on the ground and beating up animals until killing them. The victims defended themselves by trying to beat these spirits and avoiding going out at night.

History of the contact

The Botocudo original territory was the Atlantic Rain Forest in the Lower Recôncavo Baiano – the area around the Todos os Santos Bay, in the State of Bahia. They were expelled from the coast by the Tupi, and occupied a parallel stretch of forest between the Atlantic Rain Forest and the edge of the Brazilian Plateau. In the 19th Century they moved south, reaching the Doce River, in the States of Minas Gerais and Espírito Santo.

Since their earliest contacts with the Europeans, in the 16th Century, the Botocudo were accused of being cannibals, which the existing documentation does not confirm. However, that was always the main pretext to justify the frequent declarations of “Just War” against them. It was also the argument used to convince the indigenous groups that were constantly in confrontation with the Botocudo – Tupi, Malalí, Makoní, Pataxó, Maxakalí, Pañâme, Kopoxó and Kamakã-Mongoió – to aldear (be put in villages), along with promises of protection and of access to goods of the dominating society, such as fire guns. Despite their tenacious resistance, the Botocudo groups were aldeados by military men, civilian directors and religious missionaries in different points of the then Captaincies of Bahia, Minas Gerais and Espírito Santo after “Just War” was declared by the Colonial government in three Royal Letters, all of them issued in 1808. The first, dated of May 13, declared offensive war against the Botocudo of Minas Gerais because they were considered irreducible against civilization and because defensive war did not result in the desired effects regarding ensuring the expansion of the Conquest in the Captaincy.

The second, of August 24, gave permission to the Governor and Captain-General of Minas Gerais to create a troop specialized in the combat against Indians, in order to wage the war previously declared. The third, of December 2, established plans as to how to promote the religious education of the Indians and how to ensure effective control over them as a way to make possible the navigation of the rivers and the cultivation of the fields occupied by the Botocudo. The Portuguese regent, Prince João, also authorized the confiscation of the Botocudo lands, which were to be considered vacant and should be distributed as land grants, particularly among those who stood out in the war. To these new proprietors was assured also free access to the labor of the Indians who were captured in a hostile attitude, for a period that varied from twelve to twenty years, depending on the degree of rusticity and on the difficulty of the prisoners in learning their tasks. The creation of aldeamentos (villages) administered by regular citizens to educate the Indians who agreed to be submitted and showed "interest and good disposition" was also permitted. Although the three Royal Letters referred specifically to the Captaincy of Minas Gerais, in the same year of 1808 their determinations were extended to the Captaincies of Bahia and Espírito Santo, whose governors had demanded the same powers. The area currently belonging to the Krenak was given to them in 1920 by the SPI.

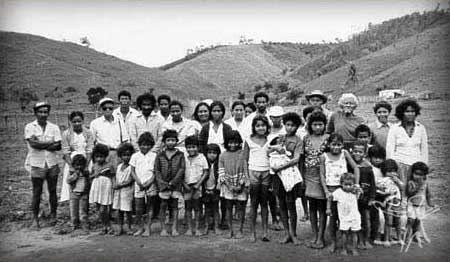

Nowadays the Botocudo do Leste are less than 200, and its population is comprised mostly by children and youngsters who descend from interethnic relations between the Krenak and other indigenous groups, such as the Guarani and the Kaingang, and with the regional population.

Several reasons explain this predominance of mixed bloods. For one, the invasion of the Krenak lands by non-Indians and the leasing by the SPI of the lands of the Krenak Indigenous Post. Also, the resettlements promoted by the SPI and by the organ that succeeded it, the Fundação Nacional do Índio – National Foundation for the Indian – (Funai): in 1953, the Krenak were removed to the Maxakalí Indigenous Post, from where they returned on foot in 1959, and in 1973, they were taken to the Fazenda Guarani. Last but not least, the contact with the so-called índios infratores (delinquent Indians), removed by the Funai from various parts of the country, starting in 1968, to the Reformatório Agrícola Indígena (Indian Agricultural Reformatory) or Centro de Reeducação Indígena Krenak (Krenak Center of Indigenous Re-education), built in the Krenak territory.

Krenak Center of Indigenous Re-education

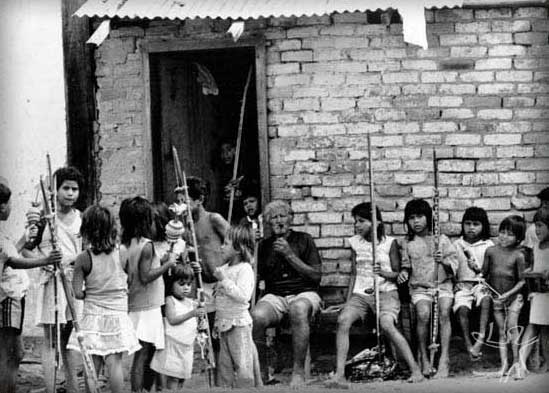

The Reformatory was implemented when the Krenak Indigenous Post was administered by Capt. Manoel Pinheiro, of the Military Police of the State of Minas Gerais, when Brazil was under a military dictatorship. It was built to receive Indians who resisted the orders of their villages’ administrators or that were considered socially deviant. There they were kept under a prisoner’s regime, being put in solitary cells and suffering physical punishments in case of rebellion. During the day they worked in the fields, under the surveillance of military policemen and of Indians that belonged to the Guarda Rural Indígena – Indian Rural Guard – (Grin), also a Capt. Pinheiro creation.

The Grin was comprised by Indians that Capt. Pinheiro defined as having "exceptional behavior." They were trained and put in uniform, and were in charge of keeping the villages’ internal order, preventing non-authorized movements of people, distributing tasks among the villagers and denouncing violators to the local Military Police detachment.

In the face of pressures from local landowners and politicians for the extinction of the Krenak Indigenous Post and the liberation of its area for the issuing of land titles to the leasers, Capt. Pinheiro made an agreement with the Minas Gerais State government in December of 1971, even though earlier that year the Krenak had won a judicial dispute that ensured them the property of their 4,000-hectare area and determined the removal of the leasers from it within 15 days. Instead of the removal of the leasers as determined by the Judiciary, he agreed to exchange the Krenak area for the Fazenda Guarani (Guarani Farm), in the municipality of Carmésia, which belonged to the Military Police of the State of Minas Gerais, where the Krenak and the Indian prisoners were transferred to. It is important to note that the Fazenda Guarani – which had been previously used as a torture center of political prisoners – was itself occupied by leasers and posseiros (illegal settlers). Although the agreement established that the Fazenda Guarani was to be handed out to the Funai without its occupants, Capt. Pinheiro did not wait for this clause to be fulfilled. Because of this, he was formally reprehended by the Funai’s presidency.

When the Krenak resisted being transferred once again, Capt. Pinheiro determined that the Indians who refused to leave their area should be manacled and taken by force to the city of Governador Valadares, in the northeastern part of the State of Minas Gerais, where the seat of the Funai’s Ajudância Minas-Bahia – Funai’s regional office for the States of Minas Gerais and Bahia – was located. From there, all the Krenak, along with the prisoners of the Reformatory and a group of Guarani Indians from Parati, in the State of Rio de Janeiro, who had joined the Krenak in their area in 1969 were put in trucks and taken to the Fazenda Guarani. If the Krenak did not like their new home from the start, their displeasure increased after the arrival of a group of Pataxó Indians from the Barra Velha Indigenous Post, in the State of Bahia, which still live in the Fazenda Guarani.

Complaining of the terrible living conditions, of the fact that the area had no major river where they could fish – the most honorable way of getting food for the Krenak –, of the climate that they considered too cold, of their poor harvests due to the depleted soils, of the forced cohabitation with the Pataxó, the Guarani and the prisoners of the Reformatory, as well as of the absence of clay to make pottery, some Krenak families decided to move to the Vanuíre Indigenous Post, in the State of São Paulo, to the city of Colatina, in the State of Espírito Santo, and to Conselheiro Pena, in the State of Minas Gerais.

Return to the land

In 1980, the remaining Krenak decided to go back to their former Indigenous Post. However, this was no easy task, since the entire area now belonged to the old leasers, who had even been given land titles to the lots they occupied. Even the Post’s former administrative headquarters had been handed over by the Ruralminas, the State organ responsible for land affairs in Minas Gerais, to the Patronato São Vicente de Paula, from the town of Resplendor, which had turned it into an orphanage.

Despite this grim scenario, 26 of the 49 Krenak who had been taken to the Fazenda Guarani returned to the area on the Doce River, establishing themselves, on their own, in 68,25 hectares, which included the ruins of the first Indigenous Post headquarters, which was not being used by the Patronato São Vicente de Paula, and in the old Reformatory.

The returned Krenak remained in this exiguous area until 1997, when , after a long judicial dispute, the Federal Supreme Court annulled the land titles given to the leasers by the Minas Gerais State government and gave the original 4,000 hectares back to the Indians.

Leadership and factionalism

Prior to the return of the area to the Indians, when arriving at the Krenak village one could see the houses of the group led by Laurita Félix to the left, a stretch of unused land in the middle, and those of the faction led by the cacique (chief) Hin – José Alfredo de Oliveira, also known as Nego – to the right, on the banks of the Eme Creek. Currently Félix’s group is settled in the farms located near the Doce River, while Hin’s group is established in the “back” of the Reserve, behind the Cuparaque Mountain Range, which crosses the area from East to West.

The fact that one of the groups is led by a woman is perfectly coherent with the Botocudo tradition, in which women have the decision power over the important internal questions.

In terms of external representation, however, it is the cacique who has active voice. In accordance to the tradition, Félix is preparing her son, Rondon Krenak, to become cacique, so that through him she will be able to have power over the group.

The opposition between the two social halves organized in political factions is diluted by the rules of exogamic marriage among the four extensive Krenak families – Isidoro, Félix, Damasceno and Souza. By establishing matrimonial alliances, the Krenak manage to ease up the conflicts and thus a relatively amicable relationship is established between the families and, by extension, between both groups. The children born out of the unions receive the father’s family name and are identified as members of the half to which he belongs. The exceptions are the inter-ethnic marriages in which the mother is a Krenak: although the family name is the father’s, the offspring are identified with the mother’s group.

One of the explanations for the power dispute between the two Krenak groups stems from the fact that the members of the group led by Félix are Nakre-ehé and Miñajirum, from the Pancas village, and never integrated completely with the cacique Hin’s group, which was originally established on the Eme Creek. To support her claim to leadership, Félix argues with the power Krenak women have traditionally had and with the fact that it is them who hold the knowledge of the group’s history, of its language and its rituals.

Besides Félix, there are other representative Krenak women, such as her daughter Marilza, who is the group’s shaman, and Sônia and Paula, who are allied with the Félix family. All of them are involved in the efforts to revive the Borun language, the chants and rituals and the usage of socializing the children through traditional methods. In this revival process, the role of Marilza Félix is extremely important. As the group’s sole shaman, she claims to be the spokesman of her predecessor Krembá. In fact, she attributes to Krembá the order that the group must be reorganized, has to “dance” its rituals again, make bows and arrows, cure their illnesses in the traditional ways, speak its ancient language and rescue the sacred mast – taken from the village in the 1930s by anthropologist Curt Nimuendajú –, which, despite the efforts, has not been located.

In this new context, thus, the Marét have lost their importance in the Botocudo pantheon, even though the fear of the Nanitiong and of the spirit of the dead, which have not gotten ritual foods and care, is still present. Nowadays the Tokón have taken the central place in the Krenak religious universe, and are deeply involved in the political dispute between the two halves.

The main challenge the Krenak face today is to adjust to their new/old area and make its economic exploration viable, despite the low population density and the lack of resources to invest in order to make their participation in the regional market possible. Such plans, in any case, are jeopardized by the opposition and prejudice shown by the dwellers of neighboring towns, who resent the fact that the lands were returned to the Indians.

Notes on the sources

The earliest reference to the Botocudo date of the 16th Century, when chroniclers and Jesuits referred to them by the name of Aimoré. Under the denomination of Botocudo, there is vast documentation of administrative character as well as texts written by naturalist voyagers starting in the beginning of the 19th Century.

With the name of Krenak, the first references date from the beginning of the 20th Century and are associated with the construction of the railroad connecting Vitória, in the State of Espírito Santo, to the present-day city of Governador Valadares, in northeastern Minas Gerais. The references were made by people in charge of the construction, such as Ceciliano Abel de Almeida, as well as by the SPI staff members in charge of aldear the Krenak, especially the reports by Antônio Estigarribia, and of the Minas Gerais State government officials charged with studies needed for the demarcation of the area to be set aside for the creation of the aldeamento.

It was only after the 1920s that scholars started to describe the Krenak society, with special emphasis to the works of Nelson de Senna and Simoens da Silva. Geographers such as Walter Egler and William Steains, who studied the peopling of the region of the Doce River also made references to the Krenak.

Linguists Charlotte Emmerich, Ruth Monserrat and Lucy Seki studied the Borun language.

There are also works by students from the Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora and the Universidade Federal da Bahia, as well as the research by Maria Hilda Baqueiro Paraiso, including one of the topics discussed in her Ph.D.’s dissertation.

The video Erré Krenak is targeted to school age children. Through it, kids learn about the history of the Krenak people; the idea is to lessen the existing prejudice and discrimination against the Indians. The video is an independent production directed by Nívea Dias and Alessandro Carvalho, with screenplay by Rita Espeschit and art direction by Cristiane Zago. Sponsored by the Indigenista Missionário Leste and the Elói Ferreira da Silva Documentation Center, with the support of the State Secretary of Culture of Minas Gerais, it is 20 minutes long and was released in the beginning of 1999.

Sources of information

- ALMEIDA, Ceciliano A. de. O desbravamento das selvas do rio Doce : memórias. Rio de Janeiro : José Olímpio Ed., 1978.

- ALMEIDA, Maria Inês de (Coord.). Conne Pãnda - Ríthioc Krenak : coisa tudo na língua krenak. Belo Horizonte : SEE-MG ; Brasília : MEC/Unesco, 1997. 68 p.

- ALVIM, Marília C. de M. Diversidade morfológica entre os índios botocudos e o “Homem da Lagoa Santa”. Rio de Janeiro : Univer. Estadual da Guanabara, 1963. (Tese de Livre Docência em Antropologia Física)

- ARAÚJO, Benedita Aparecida Chavedar. Análise do Wörterbuch der Botokudensprache. Campinas : Unicamp, 1992. 114 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado )

- ARAÚJO LEITÃO, Ana Valéria Nascimento. Por unanimidade, a reconquista da terra Krenak. In: RICARDO, Carlos Alberto (Ed.). Povos Indígenas no Brasil : 1991/1995. São Paulo : Instituto Socioambiental, 1996. p. 695-6.

- CORREA, José Gabriel Silveira. A ordem a se preservar : a gestão dos índios e o reformatório agrícola indígena Krenak. Rio de Janeiro : UFRJ, 2000. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- DUTRA, Mara Vanessa et al. Krenak, Maxacali, Pataxó e Xakriaba : a formação de professores indígenas em Minas Gerais. Em Aberto, Brasília : Inep/MEC, v. 20, n. 76, p. 74-88, fev. 2003.

- EGLER, W. A. A zona pioneira do norte do rio Doce. Boletim Geográfico do IBGE, Rio de Janeiro : IBGE, n. 167, p. 147-80, 1962.

- EMMERICH, C.; MONSERRAT, R. Sobre os Aimorés, Gren e Botocudos : notas lingüísticas. Boletim do Museu do Índio, Rio de Janeiro : Museu do Índio, n. 3, 45 p., 1975.

- KRENAK, Ailton. Recuperação física e ambiental da terra Krenak. In: RICARDO, Carlos Alberto (Ed.). Povos Indígenas no Brasil : 1991/1995. São Paulo : Instituto Socioambiental, 1996. p. 697-9.

- MANIZER, Henri. Los botocudos. Arquivos do Museu Nacional, Rio de Janeiro : Imprensa Nacional, n. 22, p. 243-73, sep., 1919.

- MATTOS, Izabel Missagia. Borum, bugre, krai : constituição social da identidade e memória étnica Krenak. Belo Horizonte : UFMG, 1996. 196 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- --------. "Civilização" e "Revolta" : povos botocudo e indigenismo missionário na província de Minas. Campinas : Unicamp, 2002. 577 p. (Tese de Doutorado)

- MOREIRA, G.; NORONHA, P. Sujeição e dominação : a dramática experiência dos Krenak. Juiz de Fora : s.ed., 1984. (Datilografado)

- PARAÍSO, Maria Hilda Baqueiro. Os botocudos e sua trajetória histórica. In: CUNHA, Manuela Carneiro da (Org.). História dos índios no Brasil. São Paulo : Companhia das Letras/SMCSP, 1992. p. 413-30.

- --------. Os Krenak do rio doce, a pacificação, o aldeamento e a luta pela terra. Rev. de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas, Salvador : UFBA, v. 2, s.n., p. 12-23, 1991.

- --------. Laudo antropológico pericial relativo a carta de ordem n. 89.1782-0 oriunda do STF e relativo à Área Krenak. Salvador : UFBA, 1989. 115 p.

- --------. Repensando a política indigenista para os Botocudos no século XIX. Rev. de Antropologia, São Paulo : USP, v. 35, p. 75-90, 1992.

- RICCIARDI, Mirella. Vanishing Amazon. Londres : Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1991. 240 p.

- SEKI, Lucy. Notas para a história dos botocudo (Borum). Boletim do Museu do Índio, Rio de Janeiro : Museu do Índio, n. 4, 22 p., jun. 1992. (Apresentado na IX Reunião da Anpocs, Curitiba, em 1986).

- SENNA, Nelson de. Indígenas de Minas Gerais : aspectos sociais, políticos e etnológicos. Belo Horizonte : Imprensa Oficial, 1965. 186 p.

- --------. Nomenclatura das principais tribos do Brasil quer das extintas quer das ainda existentes. Rev. do Arquivo Público Mineiro, Belo Horizonte : Arquivo Público Mineiro, n. 16, p. 313-21, 1910.

- --------. A terra mineira, corografia do estado de Minas Gerais. Belo Horizonte : IOF, 1927.

- SILVA, Simoens da. A tribo dos índios Krenak (botocudos do rio Doce). In: CONGRESSO INTERNACIONAL DE AMERICANISTAS (200). Annaes. v. 1. Rio de Janeiro : Imprensa Nacional, 1924. p. 65-84.

- SILVA, Thaís Cristofaro Alves da. Descrição fonética e análise de alguns processos fonológicos da língua Krenak. Belo Horizonte : UFMG, 1986. 111 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- SOARES, Geralda Chaves. Os Borun do Watu : os índios do rio Doce. Contagem : Cedefes, 1992. 198 p.

- STEAINS, William John. A exploração do rio Doce e seus afluentes da margem esquerda. Rihges, s.l. : s.ed., n. 35, p. 103-27, 1984.

- VIEIRA FILHO, João Paulo Botelho. Cetoacidose diabética em índio Krenak. Rev. da Ass. Med. Brasil., s.l. : Ass. Med. Brasil., v. 38, n. 1, p. 28-30, jan./mar. 1992.

- Erré Krenak. Dir.: Nivea Dias; Alessandro Carvalho; Cristiane Zago. Vídeo cor, NTSC, 20 min., 1998. Prod.: Cimi Leste; Centro de Documentação Elói Ferreira da Silva.

- Tikmu’un (nós, humanos). Vídeo cor, VHS-NTSC, 60 min., 1999. Prod.: Crystal Vídeo Comunicação Ltda