Tapayuna

- Self-denomination

- Kajkwakratxi

- Where they are How many

- MT, PA 432 (Amigos da Terra, 2024)

- Linguistic family

- Jê

“We need to tame the whites, who are most savage.”

This was a phrase frequently heard by the Jesuit missionaries during their contacts with the Tapayuna¹.

The Tapayuna originally lived in the region of the Arinos River, close to the municipality of Diamantino in Mato Grosso. Their traditional territory included a wide variety of natural resources, such as rubber trees, minerals and timber, which is why their land was usurped innumerable times by rubber tappers, prospectors and loggers, among other non-indigenous invaders.

In the 1970s the group was given poisoned tapir meat by invaders. The 41 survivors were transferred to the Xingu Indigenous Park, living at first in the village of the Kĩsêdjê (previously known as the Suyá) who also speak a Ge language.

In the 1980s following the death of an important leader and shaman, part of the Tapayuna people went to live with the Mebengôkrê (Kayapó) in the Capoto-Jarina Indigenous Land. The fact that the Tapayuna lived in Kĩsêdjê and Mebengôkrê villages caused a weakening of their own language and culture.

In 2010, the population was estimated at around 160 people who were distributed in villages in the Wawi Indigenous Land and the Capoto-Jarina Indigenous Land.

Notes

(1) “Beiço-de-Pau não atira para matar” (Gontran da Veiga Jardim). In: Correio da Manhã, 05/10/1967.

Names

The name Tapayuna was given to the Indians living on the affluents of the left shore of the upper Arinos River. The name was mentioned by Bartolomé Bossi, a traveller who visited the Arinos River in the nineteenth century, and by Nicoláo Badariotti, an explorer of the north of Mato Grosso, at the end of the same century.

“A ferocious tribe calling themselves the Tapañuna control the desert from the Patos river to the area around the Augusto Falls, and these Indians attack the canoes frequently” (Bartolomé Bossi, 1863).

“Zozoiaça explained to me how a few months previously the Pareci had engaged in a bloody war with the tribe of the Tapanhunas, and that they had been defeated... Zozoiaça, who took part in the combat, described the Tapanhunas as a black people with a horrible appearance who roar like beasts” (Nicaláo Badariotti, 1898).

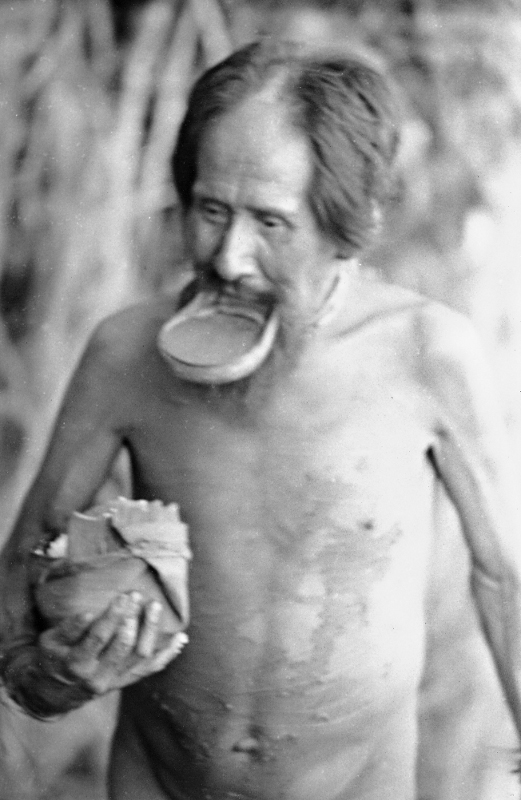

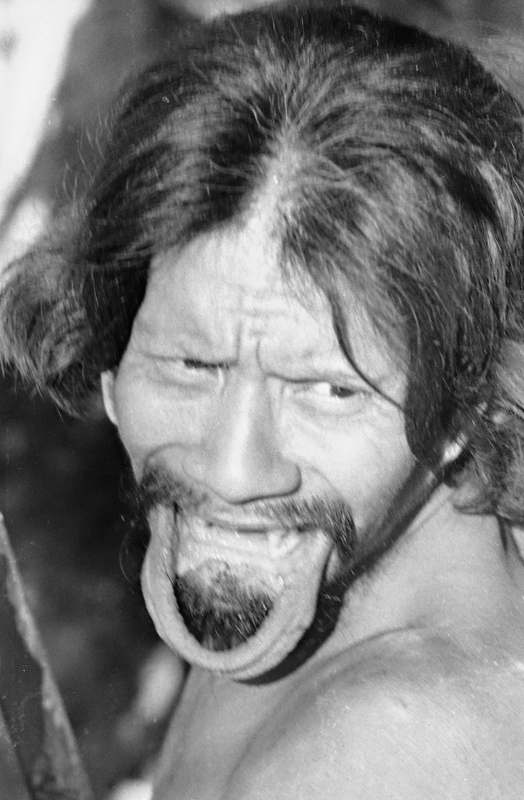

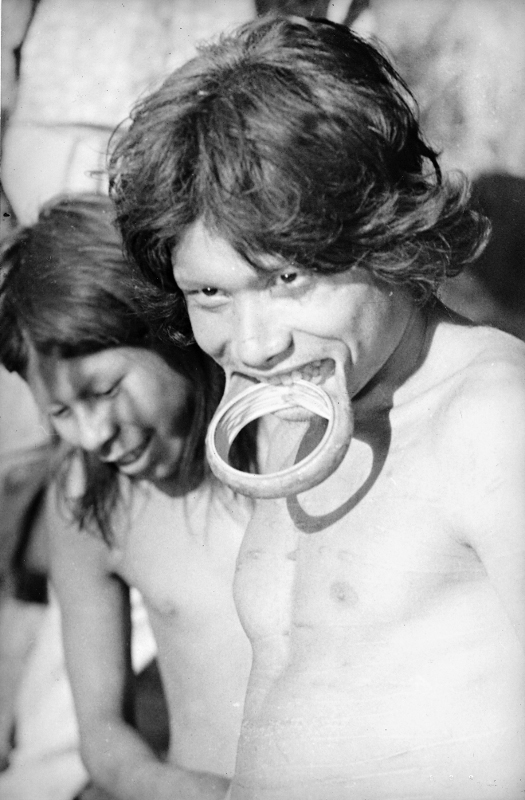

As Tapayuna men always wore a wooden disk in their bottom lip, they were called the Wooden Lips (Beiço-de-Pau) by the pioneers, the only name by which they were known in the Arinos river region.

The Tapayuna call themselves Kajkwakratxi, which means ‘trunk of the sky,’ since the people lived in the direction where the sun rises.

Location and Population

The Tapayuna have lived since the mid-1980s in the Xingu Indigenous Park and the Wawi and Capoto-Jarina Indigenous Lands, the latter the territory of the Mebengôkrê (more widely known as the Kayapó).

According to a report published in the Jornal do Brasil on November 20th 1967, Father Odílio Pedro Lunkes estimated the number of Tapayuna in the Arinos region to be around 700 people.

According to news reports published in O Globo (15/04/1969) and O Cruzeiro (19/06/1969), during a reconnaissance flight over the Arinos River, the FUNAI field officer, José Américo Peret, discovered at least 11 malocas in the region, each housing approximately 150 people, which indicated a total population of more than a thousand individuals.

The anthropologist Anthony Seeger (1974), on the other hand, estimated through genealogies a population of around 400 individuals at the time of the first contacts with FUNAI expedition members.

In 1995, the Tapayuna population in the Xingu Indigenous Park was 58 people (Escola Paulista de Medicina). In 2006, the demographic survey conducted in the Ngojhwêrê and Ngosôkô villages (Wawi IL) by Kamani Kĩsêdjê registered 57 people of Tapayuna descent or mixed Tapayuna and Kĩsêdjê descent.

In the Kawêretxikô village (Capoto-Jarina IL), on the left bank of the Xingu River, there were 98 people in 2010.

According to the estimate made by Ropkrãse Suiá and Teptanti Suiá in 2010, there were a total of 160 Tapayuna, including the populations of the two lands, Wawi and Capoto-Jarina.

Language

The Tapajúna language belongs to the Ge family, itself part of the Macro-Ge linguistic trunk.

According to Seeger (1980), the Tapayuna, also known as the Western Suyá, speak a language virtually identical to the Kĩsêdjê, the Eastern Suyá. However, there is evidence that these two languages are proximate but differences exist.

Some analyses suggest that Tapayuna is a dialectal variant of Suyá. However due to the absence of studies of the former, the similarities and differences between the two languages are not fully known.

The Tapayuna had lengthy contact with the Kĩsêdjê and the Mebengôkrê, meaning that their language has been influenced considerably by the languages spoken by these peoples.

In 2008, the language was spoken by just 40 Tapayuna living in the Capoto-Jarina IL. In 2010, there were 97 speakers in the Kawêrêtxikô village (in the same IL). Additionally the language is spoken by people who live in Ngosôkô village in the Xingu Indigenous Park.

According to Maria Cristina Cabral Troncarelli (2011), in the Kĩsêdjê village (Wawi IL), with the exception of a few older people, the younger Tapayuna adults and children speak only Suyá, which is the language used every day in the village, since their parents and other kin married with Kĩsêdjê individuals. Young people have shown an interest in learning Tapayuna and developing projects aimed at reviving the language.

Situation in the Capoto-Jarina IL

The Tapayuna language is now in a situation of linguistic attrition: in other words, it is spoken within a space dominated by a majority language, namely Mebengôkrê (Kayapó). As these languages are genetically and structurally similar (belonging to the same linguistic family), Mebengôkrê has directly influenced the speakers of the Tapayuna language. The latter, for their part, either know how to speak the two languages or only understand Mebengôkrê. In addition, we can also note the presence of the Portuguese language: the indigenous teachers leave to study outside the community and have direct contact with an environment in which Portuguese is predominantly spoken.

In fieldwork conducted in the Metyktire village in 1988, Seki recorded the exchange of some lexical data from Tapayuna for data from the Suyá language. This exchange was also observed by Santos in 1991-1992. Based on these facts, Seki (personal communication) hypothesized that even after the relocation to Metyktire, during the first few years the influence of the Suyá language spoken by the Kĩsêdjê predominated among the Tapayuna.

It is worth remembering that the Kĩsêdjê were themselves heavily influenced by the peoples of the Upper Xingu, particularly the Kamayurá, but there is no evidence that the same happened with the Tapayuna. On the other hand, it can be presumed that the Tapayuna did not make porridge and therefore borrowed the term used by the Kĩsêdjê.

The influence of the Suyá language decreased over time, though without vanishing entirely, particularly since there are Tapayuna Indians living in Kĩsêdjê villages.

The proximity of the languages, intensified by contact and by the fact that the Tapayuna comprise a minority people heavily influenced by other more powerful groups, had led to a strong pressure on the language.

It could be observed that the speakers themselves had no knowledge of the interference of the other two languages. This observation made it clear that a project needs to be implemented among the Tapayuna to enable them to gain a clearer apprehension of their own language. This awareness was awoken through the work carried out during the final stages of the Teacher Training Course begun in 1997.

Studies of the language

There are few studies on the Tapayuna language. Those that exist are fragmentary and none includes a detailed phonological or grammatical analysis. Seki (1989) made a preliminary comparison of lexical data from this language and data from both the Suyá language and the Proto-Ge. Santos (1997) contains a brief study of aspects of Tapayuna phonology, comparing them with the Suyá language. The work of C. Rodrigues e Ferreira (2007) discusses a few points concerning the reconstruction of the language, while Camargo (2004 and 2008) deals with questions related to the elaboration of a lexicographic database using the Toolbox computer program, and includes an annex with a sample containing terms for wildlife and plants in the Tapayuna language.

As well as the material gathered by Nayara da Silva Camargo, there are sets of still unpublished data collected by Seki (1989), Santos (1991-1992) and Ferreira (2003, 2004, 2005 and 2006) that were made available to the former linguist.

Some scattered material exists on Tapayuna, most of it anthropological or historical. Among the works produced by missionaries and anthropologists are historical reports made by missionaries in mid-1967, the article by Pereira (1967-1968) published in Revista de Antropologia, and studies by Bossi (1863) on indigenous groups in Mato Grosso. Important information on the Tapayuna can be found in Seeger 1981.

Linguistic revival

After their participation on the Teacher Training Course, the Tapayuna showed considerable interest in conserving their language. However, this is no easy task after so many years living among other larger populations ( Kĩsêdjê and Mebengôkrê) who speak languages very close to each other.

It is interesting to note that the interference of the Suyá and Mebengôkrê languages is more frequently evident in the speech of adult informants aged around 40. Although the speech of older people shows some interference, they also know the Tapayuna terms, which they call the ‘words of the ancients.’ Hence, this generation interferes strongly at a linguistic level, correcting the younger generations. During these moments, people discuss which term is really from the Tapayuna language.

The proximity of these three languages and the strong influence exerted by Mebengôkrê and Suyá exert on the speakers of the Tapayuna language represent difficulties for any analysis of the language, especially since there are no records of this language from the period prior to the population’s transference to the Xingu.

Until 2000, Tapayuna and Mebengôkrê youths and children from the Mebengôkrê village school studied Mebengôkrê and Portuguese, along with other subjects. Efforts were made to encourage the Tapayuna pupils to study their own language, but they showed little interest.

In 1997 the Mebengôkrê, Panará and Tapayuna Teacher Training Course was begun, promoted by FUNAI under the coordination of Maria Eliza Leite. The course’s aims included stimulating the work on indigenous languages, assisted by linguists, and valuing traditional culture. The work involved the participation of the older generations and leaders from each group. They told myths, spoke about the history of the people and their traditions, and emphasized the importance of maintaining their language and culture.

Invited to take part in the Teacher Training Course, the Tapayuna refused since they did not want to identify themselves as Tapayuna and thus rejected the work with their own language, expressing the wish to learn Portuguese and other subjects related to the world of the non-Indians.

At the same time, no linguistic studies were available to support the production of teaching materials on the Tapayuna language in the school and on the course.

This situation began to change from 2000 onwards when the Tapayuna said that they wanted a linguist to assist them with the work on their language. From this year on the group joined the course alongside the Mebengôkrê and the Panará. Over the next two years the linguists Ludoviko dos Santos and Marcelo Cazeta de Oliveira (Londrina State University) participated as advisors to the Tapayuna.

In the period from 2003 to 2006, Marília Ferreira (Pará Federal University) acted as linguistic advisor to the Tapayuna. Much of the work developed at this time was aimed at gathering linguistic data to enable the elaboration of a writing system and teaching material.

On the stage of the course held in 2007, the Tapayuna were assisted by Lucy Seki (linguistic advisor to the Mebengôkrê). During this work, an initial version was made of the first teaching material in the Tapayuna language. Considerable effort was made to make the participants aware of the importance of differentiating their language from Mebengôkrê and Suyá. The material resulted in the first literacy book in the language, which left the Tapayuna extremely proud.

In 2008, at the request of the Tapayuna, Nayara da Silva Camargo became the group’s new linguistic advisor.

In 2010, 45 Tapayuna youths and children were studying their own language.

First contacts

The contact between the Tapayuna (or Beiço de Pau, as they were known at the time) and non-Indians was undoubtedly tragic.

Until the 1940s, the reports on the people came from other groups: the Paresí, Iranxe, Rikbaktsa, Kaiabi and Apiaká. The Tapayuna lived on the shores of the Arinos River and the Sangue River in the north of Mato Grosso.

For decades they fought against the invasion of their lands and were themselves attacked: their villages were burnt and their population assassinated. Following the intensification of rubber extraction in the region of the Arinos River, a series of conflicts took place with rubber bosses and rubber tappers entering their domains.

In 1953, a batch of sugar poisoned with arsenic was left on the river shore at the order of a rubber extraction area owner from Diamantino (MT). However, the decimation did not occur only along the Arinos River. The violent clashes intensified with the advance into Tapayuna lands enabled by the opening of new roads.

In 1964, Father Adalberto Pereira, from Diamantino Prelacy, with the support of Iranxe and Paresí Indians, initiated the work of contacting the Tapayuna. That same year, along the ridge that crosses the region of the Sangue and Arinos Rivers, work began on a private road linking a farm to the BR-29 highway. The work team was made up of more than 30 men. When they arrived in the region of the Tapayuna, the conflicts began. By the end of 1964, the Indians had shot six men with arrows without killing any of them. Nobody knows, however, how many Indians were killed, given that the whites were armed.

Learning of these events, Father Adalberto entered into contact with those responsible for the work and offered to act as a mediator. He would try to ‘pacify’ the Indians with the condition that the highway workers refrained from shooting them. In July 1964, a series of contact attempts began.

The Diamantino Prelacy contact expeditions

Below is a summary of the report made by Father Adalberto Pereira, from the Prelacy of Diamantino, in which he describes the ‘pacification’ work undertaken in the Arinos river region between 1958 and 1968:

The wave of non-indigenous colonists intensified on the Arinos River, especially from 1951 onwards. As in the north of Mato Grosso as a whole, most of the landowners along the shores of the Arinos were from São Paulo state. The only asset (interest) was economic: the Tapayuna were an obstacle and incurred losses, meaning that they had to be removed immediately after pacification. The workers (labourers) with the longest and most direct contact with the conflict situation only considered one solution to the problem: the gun.

This situation persuaded the Diamantino Prelacy to ‘pacify’ the Tapayuna. As well as lessening the shock through pacification, the Prelacy’s interest lay in making the expanding wave of colonists aware of the needs and interests of the Indians too.

Since the pacification team unfortunately had to work in parallel with the advancing colonists and its opposed interests and attitudes, it needed to signal its difference to the Indians. To distinguish themselves, therefore, the pacification team’s members used conspicuously different clothing and when leaving presents always included a plastic flag with a blue monogram against a white background.

Chronology of the first conflicts with non-Indians

Rondon’s telegraph line, the construction of highways and farms close to the upper course of the Arinos River and navigation on the latter, which intensified from 1951 onwards, created a feeling among the Tapayuna of being surrounded by the whites, whose approach generated a series of conflicts. The main of these were as follows.

1931 – The Tapayuna attacked and destroyed the Parecis Telegraph Post, 80 kilometres from Diamantino.

1936 – Attacks on non-Indians who close to the line where it crossed the Sangue River and another point between Parecis and Barão de Capanema.

1937 – Guards on the Rondon line were attacked on the headwaters of the Canta Galo stream and retaliated, killing one Tapayuna man.

1945 – A guard on the Rondon line attacked by the Tapayuna while he was working in the swidden shot and killed two Indians.

1948 – In May, Father Roberto Bannwarth S. J. from the Diamantino Prelacy was in the Iranxe villages, who told the priest that they had been attacked by the wild Indians. These Tapayuna attacks against the Iranxe were one of the reasons for the diminution of the already small Iranxe group.

1951 – Benedito Bruno Ferreira Lemes, a rubber extraction area owner and twice mayor of Diamantino, constructed the ‘Boa Esperança’ work base at the confluence of the Alegre and Arinos rivers in order to harvest the rubber trees found along both. The Tapayuna burned down the base whenever they found the site uninhabited. Bruno then abandoned the area, deciding to harvest the latex on the lower course of the Arinos, instead, where he came across the Rikbaktsa Indians.

1953 – The crew of a boat belonging to Benedito Bruno, in the charge of Marcelo da Cruz, left sugar poisoned with arsenic for the Indians to take on the Barrinha River, between the Miguel de Castro and the Tomé de França streams.

1955 – The company Colonizadora Noroeste Matogrossense (Conomali), owned by Irmãos Mayer Ltd. Based in Santa Rosa (Rio Grande do Sul) entered the area of the Arinos river in definitive fashion and established a centre approximately 100 kilometres downriver of the Tomé de França. The boat belonging to Conomali became a frequent target of the Tapayuna and the workers, and even the police authorities travelling on the boat, very often responded with gunfire.

1956 – In February the pilot of Benedito Bruno’s boat was injured in the leg by an arrow. In November an engineer from Conomali was struck by another Tapayuna arrow. Thereafter Conomali decided that in the most dangerous places the boat would travel at night.

1958 - A rubber tapper was killed by the Indians and Father João Evangelista Dornstauder was struck he travelled up the Arinos river.

First attempts at peaceful contact

The first attempt at pacification began provisionally at the end of 1958 and the start of 1959 in a joint action by the Prelacy of Diamantino, the Indian Protection Service (SPI) and some volunteers.

The pacification team was maintained until May by the interested companies while the SPI prepared to enter the area definitively. The leader and advisor to this first attempt was Father João Evangelista Dornstauder, who set up a base on a sandbar of the Miguel de Castro stream where he encountered an engineering team surveying the same stretch of water. The priest named the site ‘Caaró Camp.’ There they saw the remains of a ranch belonging to Conomali (Colonizadora Noroeste Matogrossense Ltd.) destroyed by the Indians and a warehouse owned by Benedito Bruno, burned down three times by them.

Presents were left in the Tapayuna swiddens and camps and on their paths, along with a pacification sign. With achieving any direct contacts with the Indians, this team was dissolved and the SPI team promised for May 1959 failed to appear.

Between the first and second attempts, new conflicts occurred in the region inhabited by the Tapayuna.

In September 1962, Germaine Lucie Burchard began work on a new road along the ridge between the Arinos and Sangue rivers. At kilometre 139, the road cut across a trail of the Tapayuna that probably linked these two rivers. The Indians reacted and shot four workers with arrows on different dates.

In 1964, faced by this situation, Renzo Michelotto and João Galvão de Almeida, the engineer and contractor for the road in question, went to José Batista, head of the Regional Inspectorate (Inind) of Cuiabá, demanding that some kind of measure be taken. Renzo then turned to the army, specifically the 16th Battalion of Cuiabá, and received heavy weapons with the recommendation to defend himself.

The road continued to be patrolled. The guards for the machadeiros [responsible for clearing the forest and constructing the road] took up their posts a few metres from the work site with shields suspended at chest height [to protect them from arrows].

Other attempts

Aware of the situation, in 1964 Father Adalberto Holanda Pereira of the Prelacy of Diamantino met with the head of the Regional Inspectorate of Cuiabá to ask for permission to go in the place of the SPI’s employees and continue the pacification work begun in 1958.

Father Adalberto’s method was to accompany the road builders and leave presents along with the pacification symbol in strategic places on the way. The workers had no idea of the problem. Their solution was to kill the Indian men and keep the women and children. After a while, the priest would cease to accompany the roadwork in order to pursue an approach more appropriate to pacification.

There were brief encounters with the Tapayuna and various swiddens were encountered. In July 1964, it was observed that the presents left in strategic places had been taken. The team advanced a little further, presuming that the village could not be very far. One kilometre further on they saw the village in smoke. After burning it, the Tapayuna had moved away. On the clearing they found scattered many mugs and iron pans obtained from rubber tappers, as well as an old war club and a few other objects. The team went no further.

Two months later, Father Adalberto returned to the Tapayuna village and swidden accompanied by two Iranxe Indians (Maurício Tupsi and Lino Adaxi) and the Jesuit priest Cláudio Hentz. The Indians had returned to make manioc flour and had walked along the road. Some days later they encountered a Tapayuna group and after Father Adalberto spent eight minutes with an arrow pointed at him, the team decided to return to the road camp.

Almost a year later, in September 1965, Adalberto returned to the same Tapayuna swidden. The villages had disappeared and the swiddens were already overgrown. He waited a full month in the encampment at the 139 kilometre point of the road, but the Indians did not appear. Father Adalberto decided to abandon the ridge and continue the pacification work on the Arinos River.

The fourth attempt took place at the end of 1965. The priest began by flying over the left shore of the Arinos River. He located a village on the slopes of the Barrinha River and another larger village on the headwaters of the Tomé de França, dozens of kilometres from the Arinos River. The village on the Tomé de França had seventeen large swiddens.

At the end of December 1965, Father Adalberto entered the area via the Arinos river, accompanied by the Jesuit priest Luiz Carballo and João Pereira, Maurício Tupsi (Iranxe) and João Takumã ( Kaiabi).

A worker who had been surveying a property nearby gave Father Adalberto a letter from Father Henrique Froehlich, dated January 6th 1966. It read, “This is just to inform you that yesterday I received a strongly-worded telegram from the SPI against pacification, demanding that you suspend the work immediately. For now await further orders. Salutations.”

There were rapid contacts with the Tapayuna, exchanges of presents and a few arrows aimed at the pacification team.

In Brasília Father Froehlich met with the head of the SPI and reached an understanding that the Prelacy of Diamantino would continue the pacification work. In July 1966, the head of the Sixth Regional Inspectorate, Hélio Bucher, ordered a public notice to be displayed in the Diamantino Registry Office prohibiting entry into the Tapayuna lands between the Miguel de Castro and Tomé de França rivers by anyone unauthorized by the SPI.

In May 1967, new pacification work was begun. Father Adalberto was this time accompanied by the Indians Pedro (Paresí), Inocêncio (Iranxe) and Lino Adaxi (Iranxe) and by Father Antonio Iasi. This time Adalberto was shot in his right thigh during a series of attacks with arrows.

In March 1968, FUNAI authorized Father Iasi, now responsible for the Tapayuna on the part of the Prelacy of Diamantino, to intervene in the Arinos area with full powers to approach and protect the Indians, with the proviso that FUNAI’s Sixth Regional Inspectorate of Cuiabá could establish a post under its own jurisdiction.

Contacts at the end of the 1960s

While they were assaying the first peaceful contacts with non-Indians in the region, the Tapayuna received poisoned tapir meat from the ‘civilized folk.’ A large proportion of the group died. In 1973, the anthropologist Anthony Seeger recorded the testimony of a Tapayuna man, Bentugaruru, concerning the slaughter. The narrative was recounted at the request of the Kĩsêdjê of the Xingu when the Tapayuna had already been relocated to the Xingu Indigenous Park:

“I told you how the bad kupen whites put some kind of poison in the tapir and all my comrades died. Almost all of us died. The whites did that to us.”

Data collected by Father Antonio Iasi revealed approximately 140 Indians at the time of the first contacts and although the Tapayuna were on friendly terms with the invading colonists, they never allowed anyone to reach their more distant villages.

In 1967, finally, the Tapayuna, tired of defending themselves and sick, peacefully approached two boatmen on the Arinos River, the Apiaká Indian Candido Morimã and Carlos Ferreira.

In 1968, FUNAI took over the work of assisting the Tapayuna, coordinated by João Américo Peret.

In 1969, FUNAI’s directorate authorized the entry of a group of journalists into the Tapayuna area. One of the reporters had flu.

“...he has come down with a violent bout of flu. If he is not isolated immediately, our report will transform into: ‘How we exterminated the Beiço-de-Pau [Wooden Lips].’ A flu epidemic among them would be a veritable massacre” (O Cruzeiro, 19/06/1969).

The reporter’s presence indeed provoked an epidemic that killed more than 100 people.

Below is a small extract from a report published by the Jornal da Tarde - O Estado de SP (14/02/1970) on the situation of the Tapayuna soon after the epidemic.

“A few days later, when Father Iasi was able to arrive, there was nobody who could resist. He counted 73 unburied corpses and calculated more than 100 had died, since the tribe had numbered almost 200 people. He and Brother Vicente Cañas only managed to assemble 40 of those who had fled; many died in the forest. In a sign of mourning, the survivors burnt down the village, threw away their weapons and left for a new site in the company of the two missionaries. They chose the small Parecis River, 200 kilometres to the south. Dispirited, they just watched as Iasi and Vicente built two wattle-and-daub cabins and two palm leaf huts and planted a maize swidden.”

In 1969, however, FUNAI itself asked the group of Jesuit missionaries from the Prelacy of Diamantino to work in the recuperation of the survivors. At the time just 41 individuals remained, in terrible conditions, without swiddens and without the strength even to stand up.

At the start of 1970, the Tapayuna, strengthened, were transferred to the Xingu Indigenous Park. Some fled from the transfer and died before any expedition could recontact them.

In the Xingu Park, the survivors were housed in the village of the Kĩsêdjê (also known as the Suyá) but the consequences of the illnesses and transference reduced the Tapayuna population even further with just 31 people left alive.

In August 1971, the ‘Tapaiuna or Beiço de Pau Operation’ was launched by the FUNAI field officer (sertanista) Antônio de Souza Campinas. The objective of the ‘operation’ was to discover the existence of Tapayuna survivors in the region of the Arinos and Sangue rivers and to evaluate the need to interdict the area as an ‘indigenous reserve.’ No survivors were found. There were just some vestiges of recent occupation: burnt villages, broken objects, human bones...

On June 9th 1976, decree n. 77.790 revoked the ‘Tapayuna Indigenous Reserve’ in the municipality of Diamantino (MT), created on October 8th 1968 (Decree n. 63.368).

Below are some extracts from the report by the FUNAI officer Antônio de Souza Campinas (1971).

"No Tapaiuna or Beiço-de-Pau Indians exist anymore inside the Reserve created for them. (…) Inside the reserve, along the Sangue River and even the Arinos River, Indians unknown to myself harvested wild produce during the summer season.”

“The Indian Tariri [who accompanied Antônio de Souza Campinas on the expedition] held his head in his hands and then struck his chest above his heart. By then he was crying as he stared at the bones, all gnawed by peccaries, remembering that among those bones were those of the girl who was going to be his wife. He said: Karái-tán-aiti-nẽnvaine Kẽre, kêtt Kue n, ‘you civilized folk killed everyone, everything ended’.”

The pacification of the Tapayuna and the press

The first items published on the Tapayuna were newspaper reports that described the invasions of non-Indians in the area traditionally occupied by the group (the Arinos River). The first report on the Tapayuna themselves dates from 1951 and mentions the abandonment of the rubber extraction area (seringal) on the middle Arinos river by employees of the rubber area owner Benedito Bruno because of the Indians’ attacks.

News reports from 1966 describe numerous violent actions carried out in the attempt to usurp the lands of the Tapayuna. Most of these were based on reports by missionaries from the Prelacy of Diamantino (see ‘The Diamantino Prelacy contact expeditions’) denouncing the massacres and violent advance of the non-indigenous population, especially hunters, rubber tappers, farmers and colonization projects approved by the Mato Grosso government. The siege conditions experienced by the Tapayuna were mentioned frequently. The following events at the end of the 1960s stand out: the construction of the Companhia Paulista highway, providing access to the tracts of land bought by São Paulo farmers in the north of Mato Grosso, which caused innumerable conflicts in the region; the advance of the rubber extraction areas and the frenetic occupation of the region supported by projects backed by the Mato Grosso state government; the besieging of the Tapayuna – to the north was the Empresa Colonizadora Gaúcha, which explored the rubber areas; to the south was the expansion of colonization coming from Cuiabá; to the east, the São Paulo farmers; and to the west, close to the Sangue river, the area occupied by the Rikbaktsa, also known as the Canoeiros.

In 1969, numerous news reports were published on the expedition to ‘pacify’ the Tapayuna undertaken by FUNAI, since the team was accompanied by a group of journalists, sent especially to cover the contact expedition.

According to a report in O Cruzeiro (19/06/1969), in 1968 the Ministry of the Interior was forced to expropriate over a thousand hectares and transform them into an indigenous reserve on lands assigned by the Federation for the exclusive use of the Indians. FUNAI’s objective in this expedition was to ascertain the exact number of Indians and calculate the area that needed to survive. In addition, the intention was to teach the Indians how to grow cereal crops and breed livestock. This would reduce the amount of land they needed and allow areas to be freed for sale. The tax incentives granted by the government to landowners in Legal Amazonia attracted investors to the region where the Tapayuna lived.

Among the news reports published during the FUNAI expedition, we can highlight the report contained in O Cruzeiro (19/06/1969), which included numerous photographs and accounts of the daily life of the journalists in the camp, as well as some erroneous ideas concerning the recently contacted group. The magazine made frequent use of a contrast between the conquest of the moon and the contact with the Tapayuna, as though the latter were at the opposite end of ‘human evolution.’ According to the report, the Tapayuna were at “a stage of civilization prior to the New Stone Age,” “cannibals in the Space Age.”

Below are all the main reports published by the Brazilian press on the expedition to ‘pacify’ of the Tapayuna undertaken by FUNAI in 1969.

Jornal do Brasil

“The pacification of the Wooden Lips I: Cannibals who like to talk” (03/06/1969). “The pacification of the Wooden Lips II: The difficult communication with the civilized” (04/06/1969). “The pacification of the Wooden Lips III: The good neighbourliness of rapid contact” (05/06/1969).

Fatos e Fotos

“In the land of the Wooden Lips” (26/06/1969).

“In the land of the Wooden Lips 2: the long wait on the Arinos river” (20/07/1969).

O Cruzeiro

Arrival in the Xingu Park

In 1969, due to disastrous contact with the ‘white pacifiers,’ 41 survivors of the Tapayuna (better known at the time as the Wooden Lips) were removed from their lands between the Arinos and Sangue rivers to join the Kĩsêdjê (who at the time numbered around 65 people) in the Xingu Indigenous Park. Another tem Tapayuna died soon after the transference from diseases.

From the perspective of the Kĩsêdjê (also known as the Suyá), however, the cultural similarities of both groups changed considerably the emphasis of their culture. The Tapayuna looked, spoke and acted like the Kĩsêdjê ancestors. Consequently the Kĩsêdjê felt stronger, more numerous and revitalized.

In the space of a year, a new village was constructed in the Ge pattern with a circle of houses surrounding a large clearing, in which the “men’s house” was located and where Ge ceremonies were performed. The Kĩsêdjê and the ‘New Suyá,’ as the Tapayuna were called, told each other their myths and compared them. They narrated their ceremonies and discovered numerous points in common.

The Kĩsêdjê attitude towards the new arrivals was ambiguous. While they were deemed ‘authentic Suyá,’ they were also considered ‘uncivilized’ since they did not know the customs and technologies of the other Xingu peoples. For example, they did not know how to process manioc in the Xinguano style, or make and row canoes, and spoke in a way considered strange and archaic, despite speaking a similar language. Consequently, they were treated with a great deal of humour and taught the new technologies.

In 1980, the Tapayuna finally felt strong enough to construct their own village in the Park, located upriver of the confluence between the Suyá-Missu and Xingu, on the right shore of the latter. Remaining among the Kĩsêdjê were just a few orphans and some adults who had married members of the former group. Many of the Tapayuna went to live with the Metyktire (a Kayapó subgroup) in the Capoto-Jarina IL.

Marriage

The oldest shaman is married to two women, the older woman Tapayuna and the younger woman Mebengôkrê (known as Kayapó). This suggests the hypothesis that the Tapayuna used to marry more than one wife, as occurs among other indigenous groups. Currently, aside from this case, the Tapayuna are monogamous like the Mebengôkrê.

There are various cases of intermarriage between the Tapayuna and Mebengôkrê.

As mentioned earlier, in accordance with the marriage rules operating among the Tapayuna, the man goes to live in his father-in-law’s house. As a result, many Tapayuna men live in the house of a Mebengôkrê family. These kinds of cases have led to a dwindling of the Tapayuna language since the couple’s children speak the mother’s language, Mebengôkrê. The same occurs with Mebengôkrê men who marry Tapayuna women where the language learnt by the children is Tapayuna.

Relations with other peoples

The Tapayuna and Kĩsêdjê recognize that in the past they comprised a single people who inhabited a region situated in the north of Goiás or in Maranhão (to the north of Mato Grosso). From there they journeyed westwards, settling in the region of the Arinos and Sangue rivers.

At an unidentified moment, a subgroup (the Kĩsêdjê) headed eastwards, travelling down the Ronuro River to the territory of the present-day Xingu Indigenous Park, passing through the region formed by the Xingu headwaters and settling eventually on the Suyá Missu River. The other subgroup (Tapayuna) remained in the region of the Arinos and Sangue rivers.

According to estimates made by Seeger (1977), these groups remained separate for around 150-200 years.

During their first contacts with the Tapayuna, the Kĩsêdjê quickly recognized that the Tapayuna language was like that of their ancestors. Over the years they had assimilated various cultural traits from Xinguano peoples, like the use of hammocks to sleep, canoes, manioc processing techniques and so on, and treated the Tapayuna with a certain superiority since they considered them ‘backward’ because of their maintenance of ancient customs. At the same time, the arrival of the Tapayuna awoke in the Kĩsêdjê a desire to return to their original traditions.

The Tapayuna relate that at the start of 1988, following the death of an important leader and shaman, many abandoned the Kĩsêdjê village and sought refuge to the north.

To enable this move, they asked for help from Megaron, who was the director of the Xingu Indigenous Park at the time. They were offered a village in the region of the Jarina River, in Mebengôkrê (Kayapó) territory. This village was unoccupied but possessed houses and productive swiddens. The Tapayuna stayed only a short time there, since they preferred to settle in Metyktire village along with the Mebengôkrê. There they occupied three houses, built close to each other and situated behind the house of Raoni, the village leader. For a long time they remained fearful and withdrawn. They ceased practicing their own dances and festivals and began to participate instead in the dances, festivals, hunting trips and other activities typical to the Mebengôkrê. In sum, the Tapayuna rejected their own language and identity.

The Tapayuna lived in Metyktire village until the start of 2009. As early as 2004, they had spoken of building their own village. This was followed by searching for a location, preparing the site and planting swiddens. After a few families went ahead, all the Tapayuna eventually relocated to the new village. This village is called Kawêrêtxikô and is situated on the left shore of the Xingu River, within the Capoto-Jarina Indigenous Land, not very far from the Mebengôkrê village of Piaraçu.

Due to the residency rules found among the Tapayuna, after marrying a man goes to live in his father-in-law’s house. This caused a certain problem for Mebengôkrê men married to Tapayuna women who did not want to leave their village.

Following the departure of the Tapayuna from Metyktire village, the Mebengôkrê living there decided to abandon the site too and built a new village, which received the same name as the previous.

Sources of information

- BADARIOTTI, Nicolas. Exploração no norte do Mato Grosso, região do Alto Paraguay e planalto dos Parecis. Apontamentos de História Natural. Ethnographia e impressões pelo padre... salesiano. SP. 1898.

- BOSSI, Bartolomé. Viaje pintoresco por los rios Paraná, Paraguay, Sn. Lorenzo, Cuyabá y el Arino tributário Del grande Amazonas, con la description de la província de Mato Grosso bajo su aspecto físico, geográfico, mineralojico y sus producciones naturales. Paris. 1863.

- CAMARGO, Nayara da Silva. Língua Tapayúna: aspectos sociolinguísticos e uma análise fonológica preliminar. Campinas: Unicamp, 2010. (Dissertação de mestrado).

- __________. “Elaboração de um Dicionário Bilíngue Tapajúna – Português”. In: Estudos Linguísticos. São Paulo, 37 (1): 73-82, jan.-abr. 2008.

- CAMPINAS, Antonio de Souza. Relatório da Operação Tapaiuna ou Beiço de Pau. 1971 (ms.)

- LEA, Vanessa R. Parque Indígena do Xingu : Laudo antropológico: Parque Indígena do Xingu. Campinas : Unicamp, 1997. 220 p.

- DAVIS I. “Comparative Jê Phonology”. In: Estudos Linguísticos. Revista Brasileira de Linguística Teórica e Aplicada. São Paulo, 1966, vol. I, n. 2. pp. 10-24.

- FRANCHETTO, Bruna. Os Tapaiuna (Suyá Ocidentais). In: Laudo antropológico: a ocupação indígena da região dos formadores e do alto curso do rio Xingu (Parque Indígena do Xingu). Abril de 1987, pp. 111-120.

- MELLO, Octaviano. Dicionário Tupi-Português Português-Tupi. São Paulo, 1967.

- PEREIRA, Adalberto Holanda. “A pacificação dos Tapayunas”. In: Revista de Antropologia, São Paulo, vol. 15-16, 1967-196, pp. 216-227.

- Programa de formação de professores mẽbêngôkre, panará e tapajúna e Associação IPHEN-RE de Defesa do Povo Mebengokre. Atlas dos territórios mẽbêngôkre, panará e tapajúna. 2007.

- SEEGER, Anthony. Nature and Culture and Their Transformations in the Cosmology and Social Organization of the Suyá, a Ge-Speaking Tribe of Central Brazil. Chicago: University of Chicago, 1974. 420 p.

- SEEGER, Anthony. Bentugaruru tells how members of his village were treacherously poisoned by Whites. 03 de janeiro de 1983 (ms.)

VIDEOS