Tembé

- Self-denomination

- Tenetehara

- Where they are How many

- MA, PA 2096 (Siasi/Sesai, 2020)

- Linguistic family

- Tupi-Guarani

The history of the Tembé is marked by intense contact with the regional population. In the past few years, in spite of the homologation of their lands, they have been forced to live alongside hundreds of 'posseiro' (illegal farmers) families and to suffer the predatory effects of the irregular actions of logging companies, large landowners and businessmen. However, far from accepting such situation, the Tembé have been struggling for the removal of illegal occupants from their territories and demanding their rights to public organ and local powers.

Name

The Tembé are the Western branch of the Tenetehara. The Eastern group is known as Guajajara. Their self-denomination is Tenetehara, which means people, Indians in general or, more specifically Tembé and Guajajara. Tembé, or its variant Timbé, is a name that was probably given to them by the regional population. According to linguist Max Boudin, timbeb could mean 'flat nose'.

Language

The Tembé and the Guajajara speak the same language, Tenetehara, of the Tupi-Guarani linguistic family. The Tembé dialect has a dictionary in two volumes by Max Boudin. The Tembé that live near the Guamá River no longer speak their Indigenous tongue. Those who live on both margins of the Gurupi River, on the other hand, know not only their language and Portuguese but also the Ka'apor tongue.

Location

It is possible to say that, in general, the Guajajara, the Eastern branch of the Tenetehara, live in the State of Maranhão, and the Tembé, the Western branch, in the State of Pará. However, a small part of the Tembé lives on the right bank of the Gurupi River, in Maranhão.

The Tembé villages are divided into three blocks. The first are those built along the Gurupi River. The villages on the river's right bank belong to the Alto Turiaçu Indigenous Land, which has 530,524 hectares and has been homologued and registered. The Guajá and the Urubu Ka´apor Indians inhabit this region as well. The Tembé on the left bank of the Gurupi River are in the Alto Rio Guamá Indigenous Land, which has 279,897 hectares and has been homologued and registered as well. In this area also live Ka´apor, Guajá, Kreje and Munduruku Indians. On this side of the river there is also another distinct block of Tembé villages, which are located in the vicinity of the Guamá River.

The third block is formed by the Tembé who live in the Turé-Mariquita Indigenous Land, which has 147 hectares, which has been homologued and registered too. It is located on the basin of the Acará River, a tributary of the Moju, which empties in the sea a little further South of the Guamá River's mouth. The location of these Tembé is the result of an advance they made, in the 19th Century, over the territory of the Turiwara Indians, with whom they lived until recently. Today, despite its name, the Tembé Indigenous Land, also on the Acará River basin but more to the South, has a population not of Tembé Indians but of Turiwara instead.

History of contact

In mid-19th Century, part of the Tenetehara of the Pindaré and Caru rivers in Maranhão, moved towards Pará to the Gurupi, Guamá and Capim rivers, originating the people known today as Tembé (and leaving in Maranhão the Guajajara). In these rivers, they were subjected to the indigenist system that was created in 1845, in which each province had a general director (there was no national indigenist organ to take care of all the Indians during the Brazilian Empire) under whose jurisdiction each village chief was. Thus the Tembé engaged in the extraction of copal oil, which was sold to the 'regatões' (merchants that sail the rivers of the Amazon Region) using the system of 'aviamento' (in which merchandise is advanced to be paid later with forest products). The 'regatões' also used the Indians to search for gold, rubber and hardwood for them, as well as oarsmen. In the extraction of copal oil, the production unit was the extensive family. Extraction was made in the forest, above the level of annual flooding, from trees that were few and widely dispersed. Those trees could not be bled in the following season, which brought a constant need to move the extensive families to areas that were still unexplored. Thus the Tembé villages were either small with a location more or less permanent, or temporarily large but with a tendency to splitting up.

The 'regatões abuses and extortions exploded into a conflict in 1861, in the Upper Gurupi, in which seven Tembé killed nine regionals. The policeman in charge of the investigations beat up the Indians and took nine children, who were sent to Vizeu. The Indians ran away and abandoned their village. The Provincial government removed the 'regatões' from the area and grouped together the dispersed inhabitants of the Trocateua village in the new village of Santa Leopoldina. In 1862, in the Upper Gurupi alone, there were 16 villages, and, in the last decade of the 19th Century, there were evidences of many Tembé groups that had not been contacted.

The assistance to the Tembé of the Gurupi River by the SPI (Serviço de Proteção ao Índio/Service for the Protection of the Indian, the Federal Government's first indigenist organ) seem to have been a consequence of the efforts then being made to attract the Ka'apor. Between 1911 and 1929, the SPI created three posts of attraction. In 1911, it installed the Felipe Camarão Post, on the mouth of the Jararaca River, a right bank tributary of the Gurupi. Part of the Tembé of that river's upper course came down to live near the post and work as intermediaries in the attraction of the Ka'apor. For lack of resources, the activities of the post were suspended in 1915, even though it was officially extinct only in 1950. Between 1927 and 1929 the SPI created two more posts: the Pedro Dantas Post, installed on the island of Canindé-Açu, near the site where the Ka'apor used to cross the Gurupi; and the General Rondon Post, on the Maracassumé River. The latter was closed in 1940, while the Pedro Dantas, where the Ka'apor were contacted in 1928, became the present-day Canindé Indigenous Land. With the SPI posts, the Tembé began to increasingly abandon the headwaters of the Gurupi and move to the river's mid course. They served the SPI as guides, oarsmen, and field laborers and in the manufacture of flour. But in the 1950s the SPI also favored the coming of regionals to work in the posts' 'roças' (planting fields). The absence of cities nearby and the difficult conditions for the transportation of agricultural production led the SPI to stimulate the exchange of products between Indians and 'regatões', to whom they provided jaguar skins, enormous amounts of river turtles, birds and various resins.

In the 1970s, when the SPI had already been replaced by Funai, a large number of Gurupi Tembé adult males were taken to work in the Transamazon Highway and in attraction fronts of other Tupi groups such as the Parakanã and the Asurini of the mid-Xingu River. This caused a reduction in the male population in the villages, which brought about a shortage of foods based on meat and fish and jeopardized ritual practices. In 1971 Funai ordered the transfer of the Gurupi Tembé to the Guamá River, but they refused to go.

As for the Tembé of the Guamá River, they remained under the influence of the 'regatões', dedicating themselves mostly to logging. In 1945, when they already maintained intense contacts with 'civilization', the SPI installed its first and only post in the region. The post operated in a regime of production for sale and for its own consumption, and the Indians were involved in agricultural services as well as in the construction of a road connecting the Gurupi and the Guamá rivers that was never finished. A small store sold foodstuffs, clothes and tools to the Indians, which were discounted from their payment. Around 1960, in order to increase production, a post chief allowed the coming to the area of colonists from a peasant front that had reached the region, which caused an intensification of inter-ethnic marriages and an increase in the use of the Portuguese language. This regime lasted until the extinction of the SPI in 1967. Along with their tasks in the post, the Indians extracted timber and sold it on their own, taking the logs downriver to Ourém. On the other hand, the presence of hunters, loggers and livestock reduced the number of game and fish.

By 1970, the post did not have any of the old projects going and was abandoned, so the Tembé started to plant again their own fields, this time in an area that had been quite deforested. Businessmen, landowners and 'posseiros' invaded their Indigenous Land. Many negotiations for the removal of the invaders were held, but they all failed. In 1978, Funai proposed the 'loteamento' (selling of private lots) of part of the Indigenous Land to the 'posseiros'. With the help of the Catholic Church's Conselho Indigenista Missionário (CIMI), the Guamá River Tembé held a meeting with their counterparts from the Gurupi in 1983, when they signed a petition against the reduction of their Indigenous Land. At the time, they were invited by Funai to move to the Gurupi area. Some of them did, but many came back after falling sick with malaria and measles.

Economic activities

Activities for subsistence and sale of production follow natural cycles - rainy season (February/August), dry season (September/January). The Gurupi Tembé have better conditions for planting their 'roças', and more abundant prey and fish. The land, the fauna and the rivers of the Guamá Tembé have been degraded by the post's projects of self-sufficiency and by the invasion of the Indigenous Land.

To obtain industrialized products, the Gurupi Tembé extract vines and resins, hunt river turtles, jaguars and alligators and search for forest products that sell well in the market of Boa Vista do Gurupi. They also raise pigs and chicken for sale. When flour production is abundant they sell some. They manufacture canoes on order and make artifacts for their own use or to be sold to Funai's shop Artíndia.

On the Guamá River, each family has its own flourmill near the 'roça' and may also use the community's mill. They sell rice, banana and especially mallow. When there is a shortage of these products, they sell manioc flour. Guamá River 'regatões' and merchants who come by truck to nearby farms buy their products. With what they earn, the Indians buy foodstuffs and industrialized products in the neighboring cities and villages of Vila de Boca Nova, Capitão Poço and Ourém.

Social organization

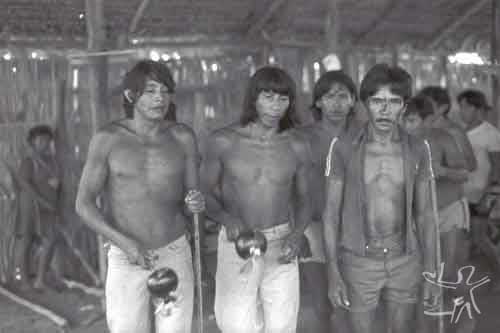

The basic unit of the Tembé social structure is the extensive family, which constitutes a production unit in itself. The family leader attracts young workers and strengthens his group through his daughters and his brothers' daughters, so that he always tries do 'adopt' women whose fathers died. The chief is thus the leader of a family group whose power is assessed by the number of individuals linked to him through kinship and matrimonial obligations, since the son-in-law must work in the 'roças' of his in-laws, with whom he lives, at least until the first child is born.

Within a wider family, the father or the widowed mother hold a position of authority. Since the public and the private spheres are not very differentiated, politics becomes domestic and a woman may lead a group in certain situations. In the 1980s, among the Gurupi Tembé, the most prestigious leader was 'captain' Verônica, and two other villages were made up of extensive families grouped around 'velhas' (old women) and widows.

The villages, whose size can vary considerably, are built on high banks along the river, near the 'roças'. The houses are covered with 'ubim' (a type of palm) and the walls made of narrow trunks of palm trees or of bark, when they exist at all. In the Indigenous post they're made of mud. Each elemental family lives in one house, and the houses that belong to the same extensive family are close to one another. Only the post's village has a large ceremonial house. In the other villages, the main space for collective use are the flourmills.

Marriage is preferably between crossed second-degree cousins that live in the same village. Marriages with regionals, which were important when the Tembé population was declining, have now been avoided in favor of unions with members of the Ka'apor, a neighboring Indigenous group.

Religion, shamanism and ritual

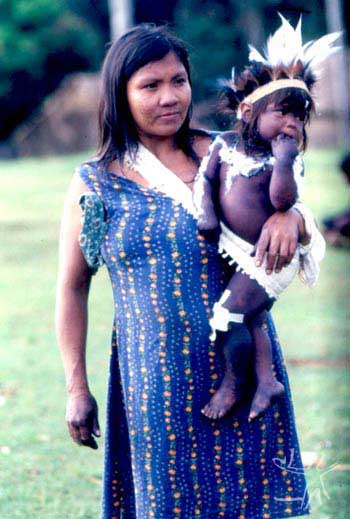

The Tembé have incorporated Christian holidays and baptism, but not Christianity as a religious system. In their mythology, Maíra is the main cultural hero and the mythical cycle of creation is the same as that of other Tupi-Guarani peoples. The spirits of the animals (especially birds), which the Tembé call piwara, are accounted for the complex eating rules that are observed in particular during puberty, pregnancy and early childhood.

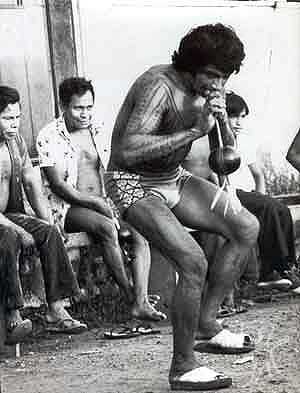

The 'pajé' (shaman), the intermediary between human and supernatural beings, calls and appeases the spirits with his half-meter cigars (tawari), chants and 'maracás' (gourd rattles). Medicines made from plants, feathers, bones or hair are given by women to those who transgress eating rules. If the treatment fails, a 'pajé', among the few that still exist, is called. Puberty rites are a good occasion for the appearance of new 'pajés'.

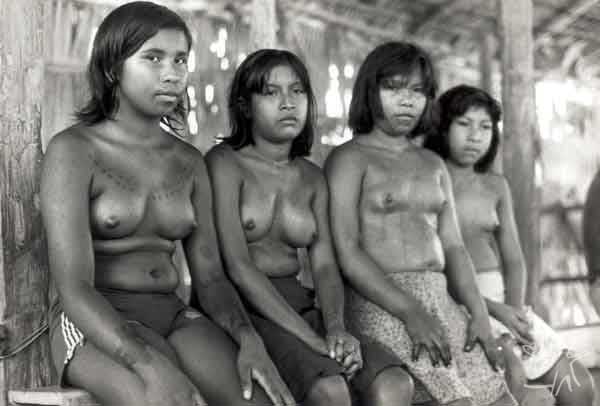

Of the old Tenetehara rites described by Charles Wagley and Eduardo Galvão in the 1940s, and today already being abandoned by the Guajajara, the Tembé keep the Wiraohavo, the puberty rite of young men and women, which was part of the maize ceremony and is also known as 'festa do moqueado'. The Tembé also perform the Wiraohavo-i (in which the i indicates the diminutive), which is the same rite but shorter and simplified; it is aimed at avoiding that the child gets sick when meat is introduced in his/her diet. Fowl, preferably 'inhambu' (a type of partridge), is killed by the father and maternal uncles for the ceremony.

Sources of information

- ALONSO, Sara Arroyo. Os Tembé de Guamá : processo de construção da cultura e identidade Tembé. Rio de Janeiro : Museu Nacional-UFRJ, 1996. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- ARNAUD, Expedito. O direito indígena e a ocupação territorial : o caso dos índios Tembé do Alto Guamá (Pará). Rev. do Museu Paulista, São Paulo : USP, v. 28, n.s., p. 221-33, 1981/1982.

- BOUDIN, Max. Dicionário de Tupi moderno (dialeto Tembé-Tenetehara do alto Rio Gurupi). São Paulo : Conselho Estadual de Artes e Ciências Humanas, 1978. 2 v.

- DODT, Gustavo. Descrição dos rios Parnayba e Gurupi (1873). São Paulo : Companhia Ed. Nacional, 1939. 223 p. (Brasiliana, 88)

- DUARTE, Fábio Bonfim. Análise gramatical das orações da língua Tembé. Brasília : UnB, 1997. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

. Construções de Gerúndio na língua Tembé. Rev. Liames, Campinas : Unicamp/IEL, n. 1, p. 77-90, 2001.

- GALVÃO, Eduardo; WAGLEY, Charles. Os índios Tenetehara : uma cultura em transição. Rio de Janeiro : MEC, 1961. 237 p. (Vida Brasileira)

- GOMES, Meécio Pereira. O índio na história : o povo Tenetehara em busca da liberdade. Petrópolis : Vozes, 2002. 632 p.

- HURLEY, Jorge. Vocabulário Tupi-Português falado pelos Tembé dos rios Gurupi e Guamá no Pará. Rev. do Museu Paulista : USP, v. 17, p. 323-51, 1931.

- LOPES, Raimundo. Os Tupis do Gurupy : ensaio comparativo. In: CONGRESO INTERNACIONAL DE AMERICANISTAS (25o.:1932: La Plata). Actas y trabajos científicos. v.1. Buenos Aires, 1934. p. 139-71.

- METRAUX, Alfred. La civilization matérielle des tribus Tupi-Guarani. Paris : Librairie Orientaliste Paul Geuthner, 1928.

. Le migrations historiques des Tupi Guarani. Journal de la Société des Américanistes, Paris : Société des Américanistes, n. 19, p. 1-45, 1928.

- NIMUENDAJÚ, Curt. Sagen der Tembé-indianer (Pará und Maranhão). Zeitschrigt für Ethnologie, Berlin, v. 47, p. 218-310, 1915.

Publicado também na Revista de Sociologia, São Paulo, n. 213, p. 174-82 e 271-82, 1951.

. Vocabulário da língua geral do Brasil nos dialectos dos Manajué do rio Ararandéu, Tembé do Acará pequeno e Turiwara do rio Acará Grande, Estado do Pará. Zeitschrigt für Ethnologie, Berlin, v. 46, p. 615-8, 1914.

- PARÁ PIGMENTOS S.A. Diagnóstico etno-ambiental dos grupos Tembé e AIs Tembé, Ture-Mariquita e Urumateua de Tomé-Açu (PA) : relatório técnico. Vitória : Cepamar, 1995. 154 p.

- PLOWDEN, James Campbell. The ecology, management and marketing of non-timber forest products in the Alto Rio Guama Indigenous Reserve (Eastern Brazilian Amazon). s.l. : Pennsylvania State University, 2001. 252 p. (Tese de Doutorado)

- RICE, Frederic John Duval. O idioma Tembé (Tupi-Guarany). Journal de la Société des Américanistes, Paris : Société des Américanistes, n. 26, p. 109-80, 1934.

- RODRIGUES, Edmilson. Comissão Especial de Estudos sobre os índios Tembé-Tenetehara da Reserva Indígena Alto Rio Guamá: Relatório Final. Belém : Assembléia Legislativa do Pará, 1994. 72 p.

- RODRIGUES, J. Barbosa. Tribo dos Tembé : índole, casamento e morte. Rev. da Exposição de Antropologia Brasileira. Rio de Janeiro : Typ. Pinheiro, 1982. 160 p.

- SALES, Noemia Pires. Pressão e resistência : os índios Tembe-Tenetehara do Alto Rio Guamá e a relação com o território. Belém : Unama, 1999. 89 p.

- SNETHLAGE, Emilie. Worte und texte der Tembé-indianer. Rev. del Instituto de Etnologia de la Universidad Nacional de Tucuman, Tucuman : Universidad Nacional, n. 2, 1931/1932.