Umutina

- Self-denomination

- Balatiponé

- Where they are How many

- MT 515 (Siasi/Sesai, 2014)

- Linguistic family

- Bororo

At the beginning of the 20th century the Umutina became the victims of violence perpetrated by non-Indians. They were described and treated by the latter as aggressive and violent indigenous peoples who used force to prevent the invasion of their tribal territory. Despite the disruptive effects caused by contact, such as the loss of their native language, their traditional territory and the diseases that led to a severe demographic decline, the people possess a strong sense of ethnic identity, recognizing themselves as traditional inhabitants of the upper Paraguai, currently committed to recuperating their traditional socio-cultural forms of expression.

Name

The Umutina were initially called ‘Barbados’ by the non-Indians due to the men’s use of beards made from their wife’s hair or the fur of the howler monkey. The group call themselves Balotiponé, meaning ‘new people.’ It was only after contact in 1930 and living alongside the Paresí and Nambikwara Indians that they became known as ‘Umotina,’ 'Omotina,’ or 'Umutina' (the written form used since the 1940s), which means ‘white Indian.’

Language

The Umutina no longer speak the indigenous language, classified as a member of the Bororo family from the Macro-Ge linguistic trunk. Its loss is associated with the violence of the contact between these people and non-Indians from 1911 onwards. After a few years a series of epidemics raged through the region, leading to the death of almost all the Umutina. The survivors began to live with the pacification team of the SPI (Indian Protection Service) working in the region and were educated in a school for Indians, which taught only non-Indian culture, barring the students from speaking their maternal language or practicing any kind of activity related to their material and immaterial culture.

Portuguese is currently the predominant language, though members of the community are using the knowledge of older people, teachers and indigenous university students to try to recover the Umutina language.

Population

In 1862 the Umutina represented a contingent of around 400 individuals. After pacification in 1911, their number fell to 300 people, but eight years later a measles outbreak further reduced the population to 200 people, living in extremely difficult conditions.

In 1923 a report from the SPI (Indian Protection Service) recorded a figure of just 120 or so people, yet by 1943 there were no more than 73 individuals, fifty of whom lived at the ‘Indigenous Brotherhood’ Post, today the main residential and administrative centre. During this same period 23 Indians were living in the last village to be found on the upper course of the Paraguai river, northern Mato Grosso, who became known as ‘the independents' because of their refusal of any form of contact with non-Indians.

Just two years later, however, a violent epidemic of whooping cough and bronchopneumonia reduced their population to 15 individuals and a short while later the few survivors also headed to the post where a series of inter-tribal marriages took place. According to information from the Umutina themselves, their current population is estimated at 445 people.

Location

In the past the Umutina lived on the right shore of the Paraguai river, roughly between the Sepotuba and Bugres rivers. The territory controlled by them, however, stretched from this zone to the Cuiabá river. With the arrival of the non-Indians, the Umutina left the Sepotuba region and migrated further north, settling on the shores of the Bugres river, called Helatinó-pó-pare by them, an affluent of the upper Paraguai. Today they live in two villages, one called ‘Umutina’ where most of their population resides (420 individuals), and another, more recent village called ‘Balotiponé,’ where another 25 people live, divided into five families. The villages are located within the Umutina Indigenous Territory in an area of 28,120 hectares ratified in 1989, situated in the municipalities of Barra do Bugres and Alto Paraguai, between the Paraguai and Bugres rivers in Mato Grosso. The IT is situated in a transitional area between Amazonia and the Cerrado, with the latter biome forming the largest part of the territory.

Contact history

Prior to pacification in 1911 by the Paulistan Helmano dos Santos Mascarenhas, at the orders of the SPI and General Candido Mariano Rondon, the Umutina were described and treated by non-Indians as an aggressive and violent indigenous people who used force to prevent invasion of the tribal territory. Their weapons were bows and arrows and a special kind of mace, called a club-sword. The attacks were launched at night and spared neither women nor children. After victory, they celebrated with singing, praising the warrior virtues of the people and recalling past victories. There are reports of ritual cannibalism.

It was around the end of the 19th century that the contacts between the Umutina and the expanding national society reached their most dramatic phase with violent clashes and deaths on both sides. According to the Salesian priest, Nicolau Badariotti, writing in 1898, the Mato Grosso government planned to organize an expedition to exterminate the Indians given the resistance they posed to the entry of non-Indians onto their lands.

The Umutina were also victims of the violence and incomprehension of so-called civilized people. Even when they approached with peaceful intentions, they were welcomed with bullets by the latter. This reaction was perhaps due to the way in which the Umutina greeted the new arrivals: the so-called 'aggressive welcome,’ when the warriors approached with drawn bows, ready to release their arrows, leaping from side-to-side and forwards and backwards, stamping their feet on the ground and yelling.

Though pacified in 1911, for a long time rubber tappers and land grabbers continued to launch attacks on the Umutina, prompting retaliations by the Indians. In 1919 they were struck by a measles epidemic, which contributed to the group’s depopulation and physical weakening. Other epidemics appeared, killing off a large portion of the population. The orphans were taken in by the staff of the indigenous post and educated by them. Today they are married, their children no longer speak their parents’ language and attend the school located in the Umutina village.

Contact between other tribal groups and the Umutina before the arrival of non-Indians in the area was either bellicose, as with the Paresí, or cordial, as with the Habusé, for example. According to the Umutina themselves, the latter people exerted a large influence on their culture.

The main descriptions of the customs and way of life of the Umutina were made by the researcher and ethnologist Harald Schultz, who lived among them at three different times in the 1940s, totalling a period of 8 months of close acquaintance with the 23 Indians still living in their own village. These gave rise to the surnames currently used by this people: Amajunepá, Amaxipá, Waquixinepá, Uapodonepá, Boroponepá, Kupodonepá, Soripa, Ariabô, Torika, Atukuaré, Pare, Bakonepá and Manepá.

“Yarepá, a veteran of bloody wars against the invaders of their lands. He is kind in nature and takes pride in knowing how to make weapons whose perfection is unmatched among the Umutina.” Upper Paraguai, Mato Grosso. Photo: Harald Schultz, 1943/44/45Contact history

Prior to pacification in 1911 by the Paulistan Helmano dos Santos Mascarenhas, at the orders of the SPI and General Candido Mariano Rondon, the Umutina were described and treated by non-Indians as an aggressive and violent indigenous people who used force to prevent invasion of the tribal territory. Their weapons were bows and arrows and a special kind of mace, called a club-sword. The attacks were launched at night and spared neither women nor children. After victory, they celebrated with singing, praising the warrior virtues of the people and recalling past victories. There are reports of ritual cannibalism.

It was around the end of the 19th century that the contacts between the Umutina and the expanding national society reached their most dramatic phase with violent clashes and deaths on both sides. According to the Salesian priest, Nicolau Badariotti, writing in 1898, the Mato Grosso government planned to organize an expedition to exterminate the Indians given the resistance they posed to the entry of non-Indians onto their lands.

The Umutina were also victims of the violence and incomprehension of so-called civilized people. Even when they approached with peaceful intentions, they were welcomed with bullets by the latter. This reaction was perhaps due to the way in which the Umutina greeted the new arrivals: the so-called 'aggressive welcome,’ when the warriors approached with drawn bows, ready to release their arrows, leaping from side-to-side and forwards and backwards, stamping their feet on the ground and yelling.

Though pacified in 1911, for a long time rubber tappers and land grabbers continued to launch attacks on the Umutina, prompting retaliations by the Indians. In 1919 they were struck by a measles epidemic, which contributed to the group’s depopulation and physical weakening. Other epidemics appeared, killing off a large portion of the population. The orphans were taken in by the staff of the indigenous post and educated by them. Today they are married, their children no longer speak their parents’ language and attend the school located in the Umutina village.

Contact between other tribal groups and the Umutina before the arrival of non-Indians in the area was either bellicose, as with the Paresí, or cordial, as with the Habusé, for example. According to the Umutina themselves, the latter people exerted a large influence on their culture.

The main descriptions of the customs and way of life of the Umutina were made by the researcher and ethnologist Harald Schultz, who lived among them at three different times in the 1940s, totalling a period of 8 months of close acquaintance with the 23 Indians still living in their own village. These gave rise to the surnames currently used by this people: Amajunepá, Amaxipá, Waquixinepá, Uapodonepá, Boroponepá, Kupodonepá, Soripa, Ariabô, Torika, Atukuaré, Pare, Bakonepá and Manepá.

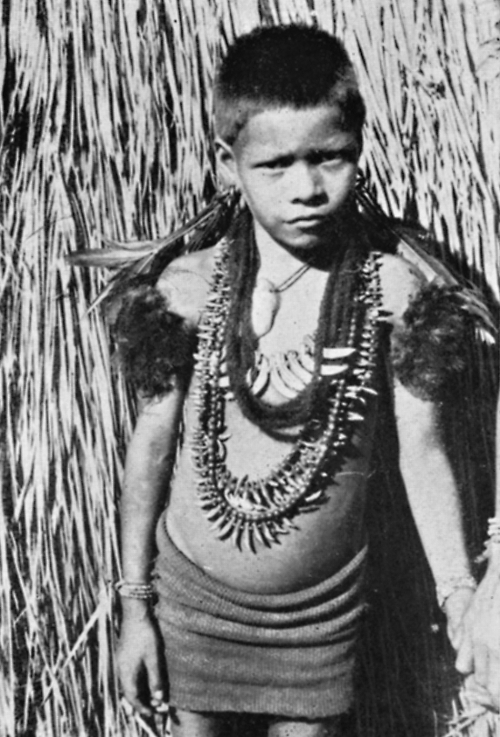

Adornments

In the 1940s, the period in which he regularly visited the Umutina, Schultz tells that the women used to wear their hair close-cropped and covered their buttocks with the ametá, a tubular dress made from hand-spun cotton woven on a very rudimentary upright loom. The men used a penis sheath and had long hair, which they tied in a knot on top of their head, rolled in a strip of cotton, similar to a small turban.

Other adornments preferred by the women included necklaces made from monkey teeth and river mollusc shells, and strings of human hair. They used pendants on their backs made from the beaks of various birds, animal claws, bones, the feathered skin of birds, small skulls and fish jaws, as well as small gourds that functioned as protective amulets against harmful spirits and diseases and that ensured their wearers a long life.

Men preferred necklaces made from jaguar teeth. The lower lip of young boys was perforated to introduce a tembetá made from the stem of a small musaceae (banana family). This decoration had to be renewed after brief intervals since it decomposed.

Body painting was constantly practiced and involved the use of both genipap, the preferred choice, and annatto. The men used designs representing the giant anteater, giant otter, neotropical otter and howler monkey, while women’s bodies were painted with designs representing fish, such as the cachara and pintado. Children were painted with designs of small fish, such as the banana piaba and three-spotted piaba (Leporinus sp.), oscar fish and catfish, as well as butterflies and leaves.

On a variety of formal occasions, such as festivals and ceremonies, the men wore animal hides on their backs, called akariká, whose use, Schultz states, seemed to be linked to socioreligious questions.

Diet

The Umutina were traditionally forest Indians specializing in agriculture, hunting and fishing. Schultz observed that despite having always lived close to rivers, they did not know how to make canoes or navigate. They crossed the water courses at fords.

According to the ethnologist, the Umutina consumed neither fermented drink nor tobacco, whether to smoke in cigars or inhale as snuff, and indeed detested its use.

The staple element of the Umutina diet was maize, which they transformed into different kinds of bread and porridge, ate roasted or cooked, or turned into unfermented chicha. Along with maize, they mainly cultivated manioc, yams, broad beans and cowpeas, banana, watermelon, peppers, cotton, annatto and a few other crops.

The forest provided them with fruit, tubers, mushrooms and wild bee honey. The animal game in their territory had already been badly affected in the 1940s by the entry of professional hunters who killed animals merely for their hides. Fishing, though, continued to be very important. They did not make traps, dams or large nets. They fished on rivers using just bows and arrows, a technique in which they were extremely adept. In the numerous fish-filled lakes they used timbó vine whose sap releases a fish poison.

Most of the Umutina IT is currently in a good state of conservation and there the population engages in swidden agriculture, providing some of the foods for their subsistence such as rice, maize, beans, yams, sweet potato, manioc, banana, watermelon and so on. The clearing, planting and harvesting are undertaken using traditional techniques. Fishing in the region’s lakes and streams also provides part of their alimentation. Around 90% of the population fish. This activity is practiced all year round with timbó, the traditional method passed on from generation to generation. The proximity of the town facilitates the purchase of industrialized goods, which guarantees most of the food consumption.

The Umutina IT is also home to many native fruit trees and a number of medicinal plants, including poaia, currently being managed. In addition, some types of honey, such as those produced by europa, jataí and borá bees, are extracted to supplement the diet.

Social organization

The group’s villages, composed of 3 to 5 houses, were located in the forest not far from the river, in a high and dry spot always close to a stream providing fresh, clean water.

At the start of the 1940s, the remaining Umutina lived in groups of nuclear families in three communal houses. The female residents of each house were consanguine kin. The marriage was arranged and decided by the girl’s parents. The intended husband had to be above all a good hunter; if not he would be rejected by the future father-in-law. If accepted, the young husband had to prove his skill as a hunter and fisherman. When men married they moved to live in their wife’s house and worked for their father-in-law. The largest house visited by Schultz contained four generations united in this fashion under the same roof.

The house and swidden were the woman’s property. If a widowed man married again, he would leave the house of his dead wife. The couple’s children would remain, though, with the family of the deceased woman to be educated and raised by them.

The Umutina told the ethnologist that they obeyed a chief only in times of war, and indeed the figure of a chief was not observed by him during his stay in the village. Normally the groups of families seemed to be led by an older woman. Alongside her, in the larger family group, there would be a man whose opinion was usually respected.

Cosmology, mythology and ritual aspects

Umutina medicine was based on a number of medicinal plants. They feared a variety of disease-transmitting spirits and avoided the consumption of capybara and paca meat since they believed that the ‘shadow’ of these rodents would cause “seizures and cramps.” Among the surviving groups there were no shamans, who seem to have been considered bad most of the time. When they became a threat to the group, they were eliminated, a fate that can be deduced from the stories that the Indians tell about them.

The Umutina myths feature the figure of Haipuku, an ancestor from whose “belly of split legs” was born an Umutina Indian couple and a Habusé Indian couple. Sun (Míni) and Moon (Hári) were companions whose adventures are narrated with gusto and humour. They emphasize Míni as intelligent, sometimes bad, and Hári as imprudent, who looked to imitate the adventures of his companion the Sun, but ended up dying a victim of his own incapacity. Míni collected the dead Moon, rolling his remains in a straw mat, which he “put to one side.” After a while, the Moon resuscitated.

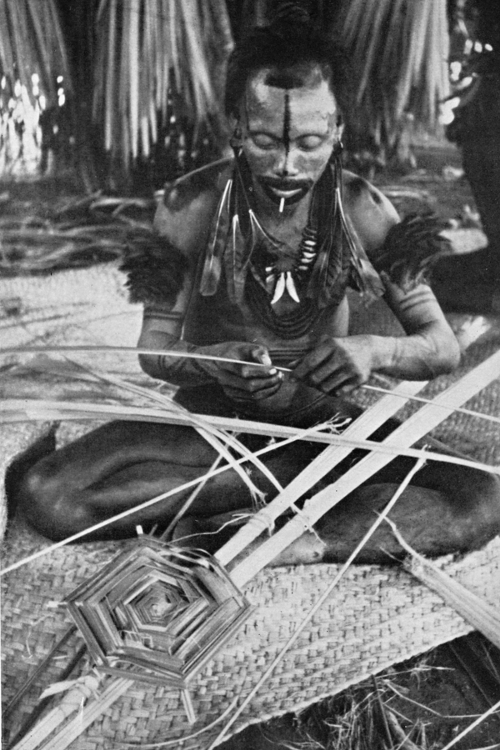

This straw mat, mentioned numerous times in the Umutina myths, is attributed with the power to resuscitate the dead. It comprises the same moriche palm straw mat which the Indians described by Schultz in the 1940s used as a seat, bed and shroud, refusing to allow strangers to use it – an object of religious importance. The mats were made only from the straw used in the costumes for the dances-rituals of the mortuary festival. Numerous legends explain the origins of the rivers, fish, animals, crops and sicknesses.

The Umutina say that they possess three souls: one of these goes to sky, the second is incarnated in animals, preferably birds, but also mammals, including even jaguars, while the third was not identified. As a premonition of their reincarnation, people see in dreams the animal that their soul is going to chose when they died. The person the tells their kin that, if he or she dies, they should obtain the animal concerned, the “carrier of the soul.” Laziness and lying are believed to be evils that prevent the eternal rest of the soul, left to wander lost through the forest without food, drink or peace of mind.

In the period when he lived among them, Schultz states that their houses were filled with various kinds of birds, such as storks, curassows, guans, eagles and macaws, which, they explained, bore the souls of deceased kin. These birds were buried with the same ceremonies as people, though in less elaborate fashion.

The dead were rolled in a straw mat and buried in their own house. The person’s kin slept above the grave. They were reluctant to abandon houses where graves were located. When forced to do so, for example in order to tend their new swiddens, cleared ever further away, these houses became cemeteries, which they tended for a while until their new houses were eventually located too far away.

At the start of the rainy season, when the ‘green maize’ was ready to harvest, they began to prepare for a large mortuary festival called adoé, which lasted 5 or 6 weeks and was made up of 18 dances-rituals. They cleared a stretch of forest and prepared a 25m x 35m dance area. At one end they would build a thatched house, called a zári, intended to “shelter the spirits of invited ancestors.” This house was barred to women. The men used it to prepare their dance costumes.

At the opposite end they built a new dwelling house. Other family groups taking part in the festival would move their houses close to the dance area, called bodod’o.

Only men who had witnessed the funerals of a kinsperson in the last annual cycle would take part in the dances-rituals. During the festivities, the protagonists of the dances would represent or embody one or several spirits of kin simultaneously.

Each dance had a name. The songs, costumes and choreography varied continually. Only moriche palm straw was used to manufacture the costumes. Some dances were apparently dedicated to the protective spirits of game, fishing, crops and so on, who were venerated like ancestors.

The festivities were coordinated by a chief who received the moriche palm straw used to make the costumes at the end of each ritual, and ordered the weaving of mats from this material by the women of his family.

Sources of information

- Demarquet, Sônia de Almeida, 1982 - Informação indígena básica IIB n. 041/82-AGESP/Funai sobre os Umutina

- Lima, Abel de Barros, 1984 - Avaliação da situação Umutina

- Prêmio Culturas Indígenas – Edição Xicão Xukuru, 2008, São Paulo, SESC-SP:

- ----------Projeto ‘Os Filhos de Haipuku’

- ----------Projeto ‘Ixipá Jukupariká - Casa de Farinha’, enviado pela Associação Indígena Umutina Otoparé (Mulheres Valentes)

- ----------Projeto ‘Noysuka (babaçu) na Cultura Umutina’, enviado pela Associação Indígena Umutina Otoparé (Mulheres Valentes Guerreiras)

- ----------Projeto ‘Zári - Casa dos Homens’, enviado pela aldeia Balotiponé

- Povos Indígenas no Brasil 2001/2005, 2006 - Instituto Socioambiental

- Schultz, Harald, 1952 - Vocabulário dos índios Umutina – Journal de la Societé des Américanistes, N.S., 41:81-137;

- ----------1953 - Vinte e três índios resistem à civilização, Edições Melhoramentos

VIDEOS