Krikatí

- Self-denomination

- Kricatijê

- Where they are How many

- MA 1031 (Siasi/Sesai, 2020)

- Linguistic family

- Jê

Krĩkati lands have been invaded by cattle ranchers since the nineteenth century. However the Brazilian state only recognized their full territorial rights in 2004 after decades of conflicts. Today they look to pursue their own way of life and worldview shared by the other Timbira peoples living in the region.

Name and Population

The group’s self-denomination is Krĩcatijê, which means “the people from the large village,” a name also applied to them by the other Timbira. Their immediate neighbours, the Pukopjê, refer to them using the designation Põcatêgê, which means “the people who control the uplands.”

Based on the combined reference to the Krĩkati and Pukopjê as a single unit in the historical sources, at the start of the nineteenth century the population of the two groups was estimated by Paula Ribeiro to be approximately 2,000 people. In 1919 a census by the Indian Protection Service (SPI) suggested a population of 273 people distributed among the villages of Engenho Novo and Canto da Aldeia.

It was only from the 1960s onwards that the populations of the two groups began to be indicated separately.

| Date | Source | Population |

| 1963 | SPI | 230 |

| 1964 | JEAN CARTER LAVE | 210 |

| 1969 | DOLORES NEWTON | 204 |

| 1970 | COTRIM / FUNAI | 146 |

| 1979 | MONTAGNER / FUNAI | 291 |

| 1984 | SANTOS | 338 |

| 1990 |

FUNAI |

420 |

| 1996 | CTI | 487 |

| 2005 | FUNASA | 682 |

Location and situation of lands

The Krĩkati Indigenous Land is located in the Maranhão municipalities of Montes Altos and Sítio Novo, in the southwest of the state. The IL is drained by the rivers and streams of the Tocantins basin (Lajeado, Arraia and Tapuio, among others) and the Pindaré/Mearim basin. In fact the headwaters of the first of these important rivers of Maranhão rises within the Indigenous Land.

In 2005 the Krĩkati lived in two villages: São José (the largest and oldest) and Raiz, the latter founded a few months after the conclusion of the physical demarcation of the area in 1999. There was also another village (Cocal) occupied by Guajajara men married to some of the Krĩkati women.

History of the process of official recognition of the IL

The Krĩkati territory was declared an Indigenous Land on July 8th 1992 through ministerial decree n. 328. This decree designated a total of 146,000 hectares to be of indigenous possession. The studies defining the limits to the Krĩkati IL were not undertaken only by FUNAI but also through an expert named by the Federal Judge of the Second District Court of São Luis, who recognized its legal validity by rejecting the claim of many farmers from Montes Altos, who filed an appeal in 1981 in an attempt to gain legal recognition of their land titles in the area claimed by the Krĩkati. The Federal Judge ruled that the deeds of the 120 farmers that had filed the appeal were invalid, rejecting the case without prejudice.

Even the experts appointed by the farmers in the lawsuit were forced to recognize that the land deeds presented “...were related to possessions without denomination, localization, borders or defined area – which nullifies the documentation presented as legal claims by the heirs or successors” (Case n. 1875/81, Second Federal District Court of Maranhão). Hence as well as the legitimacy of the indigenous possession of the area identified by the expert, the Court recognized that the would-be owners were occupants of Federal lands whose exclusive use in fact belonged solely to the Krĩkati Indians, according to article 231 of the 1988 Federal Constitution. The public authority’s omission in delaying the administrative demarcation of the indigenous area indefinitely had generated an explosive situation, placing at risk the very physical survival of the Krĩkati Indians.

In 1989, FUNAI recorded 563 occupations in the area delimited for the Krĩkati Indians, observing that in 161 cases the occupants did not live on the property (meaning that these occupants do not live solely from the property or have another source of income). Furthermore 256 of these occupations were established between 1979 and 1989 (hence after the first decree officially declaring the limits of the area) and of these a total of 96 were effected only in 1988 and 1989. In other words almost 50% of the occupations were established after the beginning of the judicial action (characterizing these occupants as acting in bad faith).

In 1999, FUNAI began the process of removing these occupants, paying for improvement to the land. However complete removal of these occupants has yet to be achieved. Meanwhile the Krĩkati are receiving a devastated land with few forests and little or no game or fish.

Contact History

...the Krĩkati never abandoned their ancient homelands to the east of the Tocantins, where this river changes direction from flowing south/north to east/west and the Imperatriz springs, in deeper forest.” (Nimuendajú 1946:19).

All the historical references to the Krĩkati (‘Caracati’) situate them precisely in the territory described by Nimuendajú: Casteneau (1844), Ferreira Gomes (1859) and Marques (1870) all do so. In his “Memoir concerning the Gentile Nations” written in 1819, Major Francisco de Paula Ribeiro mentions in passing the ‘Poncatgêz,’ a group whose territory coincides with the area historically occupied by the Krĩkati. Along with their neighbours the Pãrecamekra (who inhabited the north of the Farinha river, downriver on the Tocantins), the indigenous population was attacked in 1814 by a bandeira expedition organized in São Pedro de Alcântara and assisted by the Mãcamekra (Paula Ribeiro 1841). As well as the geographic coincidence, their name coincides with the designation given by the Gavião-Pukopjê and other Timbira to the Krĩkati: Põcatejê (“those who control the uplands”). All the indications are that the ‘Põcatgêz’ mentioned by Paula Ribeiro were in fact a more southern subdivision of the so-called Krĩkati.

Proximate both culturally and spatially, the Krĩkati were frequently confused with the Gavião-Pukopjê. This fact would explain the relatively late appearance of the term ‘Caracati’ in the historical sources and the omission made by Paula Ribeiro which, as Nimuendajú opined, was “the sole error made by this knowledgeable scholar of the ancient Timbira” (1946: 8). Observing the map of Maranhão produced by Cândido Mendes de Almeida (and published in 1868) we can note that the region between Imperatriz and the Serra da Desordem uplands is annotated with the term “Is. Gaviões.” Another important fact to observe is that since it was practically ‘unoccupied’ by farms or towns, there was little detailed geographical information on the aforementioned region, inducing the author to make some obvious mistakes (for example the localizations of the Serra da Desordem itself). In fact what the author actually knew at the time was that the area between Imperatriz and the Serra da Desordem uplands was inhabited by ‘Gaviões’ Indians.

Warrior-like and bellicose, the so-named ‘Gaviões’ (that is, the Pukopjê and Krĩkati) blocked the attempts to colonize the region between the headwaters of the Pindaré and Tocantins (the ‘Grajaú Fields’) until 1841. In 1817 the Maranhão government funded a military settlement on the shores of the upper Grajaú River, the Leopoldina Colony, to “call the region’s Indians to make peace” and allow colonization. Responsibility for executing this project fell to Francisco Pinto de Magalhães, the “successful pacifier of the Mâkamekra,” with the support of 40 frontline soldiers. However by 1821 nothing was left of this colony since Francisco de Magalhães “(...) was obliged (...) in the face of the ferocity [of the Indians] to abandon the garrison and retreat with eighteen men” (Marques [1870] 1970: 200,362).

After the installation of the military colony of Santa Thereza (today Imperatriz do Maranhão) – at the order and expense of the government of Pará state – and the establishment there of the missionary Manuel Procópio, some groups of Timbira Indians began to establish peaceful contacts with the priest:

The first people with whom [the priest] dealt were the Apinayé – but unfortunately they rebelled and abandoned the place that they had inhabited, moving deeper into the forest. He therefore headed instead to the malocas of the Caracatis, Caracatigês and Gaviões, and with more fortune was able to establish friendly relations with them, reaching the point that their Tuxãuas or chiefs promised to follow him and live in a village under his direction. As the site for settling this population, the missionary had chosen a place called Campo dos Frades, which seemed to him the most suitable” (Aguiar 1851: 57/58).

In another report we read:

The missionary of Santa Thereza de Tocantins (...) communicated to me at the end of last year [i.e. 1853] that on this occasion five hundred Indians had come down from the Sertão to their mission; (...) and recently another three hundred and two from the Cravaty tribe had joined them there.” (Rego Barros 1854: 37).

These are the main explicit references to the ‘Caracati’ in the historical sources as a group different from the ‘Gaviões’ – and it is through these sources that we also know that the first peaceful contacts with the ‘Caracatis’ only occurred in 1854. However of the ‘Caracatis’ mentioned above, few must have remained there since in the next report (1855) states that the indigenous population of the colony was just 109 (Pinto Magalhães 1855: 26).

The report by the president of the province of Maranhão in 1855 makes no reference to the colony, mentioning only the “Gavião and Caracatys Indians (...) existing on the left shore of the Grajahú river” (Olímpio Machado 1855: 58).

In 1856 another report suggested that “the missionary of the new mission of Santa Thereza (...) appealed to the Judge of Carolina District for additional forces and protection because of the threats and raids on cattle occurring on a daily basis; in his own phrase, by a thousand bows surrounding the mission” (Cruz Machado 1856: 70). The same report, however, describing the three local directorates existing in Vila da Chapada (Grajaú), cites “thirteen small villages of ‘Gaviões’ Indians who inhabit the shore of the Grajaú” (ibid: 67, 68). As the two other local directorates of Vila da Chapada were composed by ‘Matteiros’ (Xàcamekra) and ‘Canellas’ Indians, this leads us to suppose that once again the author of the report included the Pukopjê and Krĩkati under the denomination of ‘Gaviões.’

This report is significant because as well as citing the number of villages belonging to the ‘Gaviões’ on the left shore of the Grajaú, it claims that “except for [the village] of Captain Pompeu, which being very remote is unknown, all the rest communicate more or less with the Christians”, going as far as to add the detail that “the leaders of six of them already have Christian names and comprise a total of 592 Indians” (ibid: 68). Moreover the author avoids the risk of confusing the ‘Gavião’ and Guajajara villages by considering that “numerous uncivilized indigenous tribes exist throughout the forest natives conserve their original habits (...). The Guajajara are the only ones who have taking advantage of relations with our society, due in large part to the excellent disposition that they possess” (ibid: 68).

Until the start of the 1860s, at least, there is a wealth of evidence showing that the region between the Tocantins river and the left shore of the upper Grajaú river (in the Serra da Desordem uplands) was the domain of the ‘Gaviões Indians’ – as Cândido Mendes de Almeida and César Augusto Marques assert.

Today we have enough ethnohistorical material to be able to consider that the indigenous groups encompassed by the name ‘Gaviões’ were in fact:

- the ‘Western Gaviões’ ( Paracatêjê, today inhabiting the Mãe Maria IL in Pará), who until the start of the 1970s remained in isolation – part of the group at least – and controlled the northeast of Imperatriz from Frades creek to the Alcobaça (Tucuruí) river;

- the Pykopjê Gaviões, whose domain even today covers the Santana basin and the affluents of the left shore of the upper Grajaú (and who now inhabit the Governador IL – Maranhão);

- the Krĩkati (Põcatêjê), whose territory was located to the south and southeast of the Pukopjê Gaviões, on the headwaters of the Grajaú and Pindaré rivers and – crossing the watershed of the latter river – on the affluents of the left shore of the Tocantins river between the Arraia and Imperatriz rivers; and

- the Pihàcamekra (or ‘Pivocas’ or ‘Caracatigês’), whose “former centres were on the Embira Branca, a creek that flows into the right-hand shore of the Tocantins, a short way downstream of Imperatriz” (Nimuendajú 1946: 18). In 1859 Ferreira Gomes visited one of the ‘Caragés’ villages “one league from Santa Thereza, encountering there some 50 or 60 poor and malnourished inhabitants” (1862: 510). Marques, citing a document from 1862, claims that there were two villages of these ‘Caragés’ (= ‘Caracatêjês’ = ‘Pivocas’ = ‘Pivoca-Mecrãns’- Pihàcamekra) in the area surrounding Santa Thereza “(...) with their habitations spanning a quarter league and the other one league, as well as innumerable wild groups who, though inhabiting more distant places, remain in contact with these Indians” (1970 (1870): 567). A list of indigenous groups provided by the Judge of the District of Carolina to the President of Maranhão Province in 1861 cites the village of the ‘Pivocas’ on the headwaters of the Pindaré and on the outskirts of Santa Thereza (ibid: 180). As Nimuendajú comments: “the list deserves little credence... but it seems to indicate that at the time at least part of the tribe (of the Pihàcamekra) had already retreated beyond the Tocantins watershed” (1946: 18).

Krĩkati history as told by themselves: the dynamic of the villages

The memory of the contemporary Krĩkati extends back to a village situated on the Batalha River, which they refer to as the village of the Cutõi (Maracá). Following the course of the Batalha River, they formed another village, close to the lake that they call Aaprore, near to the Mentocará uplands. From there they migrated to the Hutéxãmxà uplands. These highland areas (serras) are in fact the tips of the Serra do Cocalinho.

It was during this period that, according to the older Krĩkati, the “Portuguese arrived,” or at least the presence of the whites began to disrupt and interfere in the Krĩkati process of relocating their villages and, therefore, in the occupation of the territory. They say that they left the Serra do Cocalinho for the upland plateau and formed a village close to Fortes lake (Kyprejõnku) on a headwater river of the Pindaré – close to the place where the settlement called Quiosque was located.

Constantly relocating further away because of the cupen (‘civilized’ folk), the Krĩkati say that they moved downriver as far as the São Gregório, forming the village Hõcrécaixô. While they were in this village, some Krĩkati children were abducted by the whites and, after raiding a farm to recover them, they dispersed in fear of reprisals.

Marques narrates this episode, referring to the:

lamentable facts that the Indians of the tribe – the Caracati – perpetrated at the Salto de D. Raimunda Pereira da Luz farm, which resulted in the death of the owner and another sixteen people (...) the Indians were provoked to this action by João Machado and others, whose number included three sons-in-law of the aforementioned D. Raimunda, who had invaded the village where the Indians lived and stolen three children. They later tried to hide their wicked action by barbarically murdering two Indians from those they had abducted. For these crimes they are already in prison and being prosecuted by the police chief of Carolina” (1970 [1870]: 182).

This news appears in an official letter from the Judge of Carolina at the time, Dr. Manoel Jansen Ferreira, to the person responsible for building a highway between Santa Thereza and Monção. For our own purposes it is interesting to cite the concluding section of the letter:

...moreover, those Indians (the Caracatis) live very far from the places where the highway has to pass ... Do not, therefore, be persuaded by unfounded news of aggressions and, without abandoning the measures advised by the conflict, you should be aware that the wild Indians, knowing from the tradition of their elders of the superiority that we have over them, and devoid of the resources to live in primitive independence, given that they are now reduced to a small territory and surrounded on all sides by civilized settlements, now wish and seek to live in peace, and are entirely non-violent, unless provoked” (Marques 1970 [1870]: 183).

The route of the highway cited in this letter was to pass along the Bacabatiua creek (ibid 182), thereby cutting across the territory of the Pihàcamekra. The start of the work on the highway began in 1864-65. But the account does not specify the date of the attack on ‘Salto’ farm, which, from what can be inferred from the texts listed by Marques, must have occurred some years earlier (probably in 1861).

Salto farm was situated presumably along the Salto River, which, along with the Tapuio and São Gregório rivers, formed the Arraia. Hence the report from Marques matches the historical and geographical information provided by Krĩkati oral history, which tells us that during this period (the time of the attack on the farm) one of their villages was situated on the shores of the São Gregório river (and thus occupying the basin of the Arraia river).

After this attack on the farm, the Krĩkati dispersed. One group took refuge in the Serra da Desordem, close, they say, to the site now occupied by the town of Imperatriz (formerly Santa Thereza). Once again Marques gives us a clue when he reports that:

...in April and May 1862, 300 Indians, more or less, having encountered the Tocantins highway open again, whose location bisected the forest in which they live, came with others already domesticated to the settlement of Santa Thereza to sue for peace, undoubtedly fearing the bandeira expeditions of which they had sad and bloody memories” (ibid: 180)

These three hundred Indians were probably one of the Krĩkati groups that had dispersed after the attack on the Salto farm; the “already domesticated others” would be the Pihàcamekra with whom the Krĩkati maintained relations of alliance.

While this group remained in the vicinity of the military colony of Santa Thereza, another group had taken refuge in the opposite direction, in the Serra da Desordem uplands.

The Indians recount the difficult times they had remaining in the uplands where there was little or no water. During this period (around 1866) they settled close to a ‘farmer’ called Amaro. They say that many young people, responding to the invitation and promise made by the farmer, travelled down from the uplands and never returned to the village. Finally the chief of the village, Ahyt, told another two Indians to follow at a distance the young man sent from the village in response to farmer’s invitation to discover what was happening. They say that the farmer ordered the Indians strung upside down before killing them, making them drink “hot cow tallow.”

It is interesting that this episode is recalled differently by Delvair Montagner in his report to FUNAI in 1980:

They took refuge from the ‘Christians’ (Kupê) in the Serra (da Desordem) uplands. The ‘pacifier’ Amaro scaled the Serra da Desordem to find the village and attract more Indians. The sertanejos remain in hiding and when more than twenty Indians came to get the food offered by them, they were killed and thrown in the river. The Krĩkati want to see the comrades who had gone previously. Amaro says that he killed them and that he will repay them with material goods. The Indians go away. The black man is ordered to return to the village and take the captured leader, Alexandre. These events took place close to the headwaters of the Arraia, right behind the Serra da Desordem highlands, at a site called Fortaleza.”

The present-day Krĩkati retell this episode, which occurred about a hundred years ago, with such a wealth of detail and such rapidness that it seems as though it happened yesterday. In fact reinforcing the bellicosity of the farmer Amaro can be seen as an attempt to combine into one single episode (the most illustrative) the situation of persecution in which they were found at the time and the shock of having to share a territory with groups who were complete strangers to them (to the point that they were unaware of the fate of the young men from the village who had decided to visit the outskirts of the white settlements) – territories which they had previously disputed with their indigenous peers (the other Timbira groups).

In their account the Krĩkati add that, having been discovered, the farmer gave them, as part of a peace accord, two swiddens of manioc and five corrals full of cattle. This persuaded them to come down from the Serra da Desordem and build a village on the site. From ‘killer’ to ‘friend’ of the Indians, this account summarizes the relations between the Indians and the neo-Brazilians and indicates how the whites through ‘treats’ (donating cattle, manioc swiddens and so on) established the contact with the Indians that ensured that the colonizers could stay in their territories.

The Indians recall that their ancestors told them that in the past there were no civilized folk in their habitat. They arrived slowly, asking for permission from the captain [chief] to live there. They placated him with presents and tobacco. They said that they were there friends and ‘good.’ They ate their game and destroyed the forest, which today has almost entirely vanished. They say that the ‘pacifier’ Amaro asked the captain to be able to live in the area. His son, the owner of the São Francisco Farm, asked captain Lourenço for permission to stay definitively in the place where they had settled (...)” (Montagner 1980: 5).

After the flight, contact was more systematic: this was “the start of peaceful coexistence” and the Krĩkati recount that they moved from Fortaleza village to the Tapuio River where they founded another village, Caldeirão - Hincá. A band separated from this group to form a village next to the Faveira River (close to the place today known as Quiosque). Later they returned to Caldeirão and, joining together, constructed Quati village, almost on the headwaters of the Tapuio, returning once again to the Serra da Desordem uplands.

The Krĩkati say that it was in this village that they made contact with the family of Raimundo de Souza Milhomem and asked Lourenço (Krìàkra), the great-grandson of Francisco (former ‘captain’ and an important leader among the contemporary Krĩkati) permission to live and raise cattle, and the old Indian took the Milhomem family to a place called Cana Brava. “But because of the malaria, the Milhomems moved away and went to settle in the basin of the Campo Alegre river” (very close to the present-day village of the Krĩkati, called São José). It is important to observe that, having given permission to stay on their territories, the old Krĩkati ‘captain’ began to adopted the surname of the Milhomem, transmitting this ‘right’ to their descendants.

The fact that he had settled in Krĩkati territory – in an alliance relationship with them – meant that Raimundo de Souza Milhomem was nominated in 1887 to occupy the post of Director of Indians of the Imperatriz Local Directorate, legitimizing and stimulating the occupation of the indigenous territory by his family members and offering ‘protection’ to the Indians in return.

As ‘Director of the Indians,’ Raimundo Milhomem was able to ‘placate’ the Krĩkati (i.e. pay rent to the Indians for occupation of their lands) not with his own resources but with public funds transferred to him by the provincial government. Again it needs to be stressed that the explicit purpose of the ‘Local Directorates’ was to “remove the Indians from their savage state in order to enable the civilized occupation of their immense lands.”

From the Quati village a Krĩkati group migrated to the Arraia River, forming the village of ‘Canto da Aldeia.’

In the 20th century

At this point we are roughly at the turn of the twentieth century. It was at Canto da Aldeia that the two Krĩkati subgroups joined together again. However we can back now to the movements of the other Krĩkati group that at the time of the attack on Salto farm had moved to the outskirts of Santa Thereza. We do not know the reasons why this Krĩkati group – which had sought protection from the Santa Thereza military colony – had started to return to the area from which they had retreated. What is important to stress is that this Krĩkati subgroup joined a Pihàcamekra group, a fact corroborated by the account given by Zezinho (the oldest person in the village, aged over 90) in which he said that his people left because of the measles epidemic on the headwaters of the Cacau (the territory of the Pihàcamekra group) and migrated to Imperatriz (the colony of Santa Thereza) and from there the followed the Tocantins shore as far as the headwaters of the Clementino river where they ended up settling near to the Arraia river, forming Bacuri Seco village. According to the elder Zezinho, the group that was at Imperatriz (the Pihàcamekra) “were quiet, those who were in the Serra da Desordem uplands were the ones with problems with the cupen.”

From this village – remaining always within the basin of the Arraia River – they relocated to found São João village, followed by Mata Verde village, before returning to the area of the former São Gregório village. There, a quarter of a league away from the latter site, they formed a new village also called São Gregório.

The Krĩkati say that when this group built São Gregório village, the other group was located at Faveira village. After the latter moved to found Canto da Aldeia village on the most southern headwater of the Pindaré River, the two groups began to establish more systematic relations through matrimonial connections, the search for healers or even through invitations to take part in rituals. Finally the subgroup from the São Gregório village ended up joining the Krĩkati from Canto da Aldeia.

The two groups probably decided to unite because their demographic numbers were insufficient to be able to guarantee their physical and cultural reproduction. It was when they were again united in this village that they made a large encampment (rancharia) next to a small lake alongside the Pindaré. This zone is extremely valuable to the Indians since it is rich in rãm (almácega do brejo, Protium sp.) whose sap is used in arrow making, which is why the Krĩkati regularly camp on its shores. This pool is today called ‘Poço do Caboclo Velho’ [Pool of the Old Indian] or Ramcô, because, the Krĩkati say, at that time an old Indian was killed there and thrown in the pool by the ‘Christians.’

The village located at ‘Canto da Aldeia’ is the reference point for the description and analysis of the migrations of the Krĩkati subgroups through their territory in the twentieth century as their villages split, divided, merged and split again over time.

The SPI census from 1919 mentions two Krĩkati villages – ‘Engenho Velho,’ with 65 inhabitants, and ‘Canto da Aldeia’ with 204. However Numuendajú, who visited them in 1920, refers to a third village, ‘Caldeirão,’ without, however, mentioning its population (Nimuendajú 1946: 17).

It is worth recalling that it was the Caldeirão village (next to the Tapuio, an affluent of the Arraia River) that one of the Krĩkati bands left to reside at Canto da Aldeia. A few families probably stayed at the old site. Nimuendajú probably did not visit them, explaining why he provides no estimate to their population, though he must have heard about some families who had not yet joined the rest of the group when he was at Canto da Aldeia. ‘Engenho Velho’ was formed by an extended family comprising the late Manduca (the father of the elder Ludogero, still alive) and his children and children-in-law. The trajectory of this small subgroup indicates that it remained autonomous until around 1978.

Living together again in a populous village after almost 70 years, ‘Cano da Aldeia’ allowed large-scale rituals to be performed (those linked to the initiation cycle, which require the participation not of one family group but of all the families making up the village). This was also the period when invasions of the Krĩkati territory grew apace and the Indians began to lose control of the people who were occupying their lands.

The new occupants and the descendants of the colonists ceased to pay for their occupation of ‘Indian land’ with cattle. As the cattle increased and game became scarce, the Indians began to intensify their killing of the cattle of the cupen. The threat became that isolated attacks – such as that of the old man thrown in the pool by the Pindaré River (identified as the northern border of the traditional and current territory) – could turn into full-scale ‘Indian massacres.’

In response to this situation the SPI decided, in 1929, that its officer Marcelino Miranda should seek not the expulsion of invaders and those responsible for the climate of tension from Krĩkati territory, but the transference of the Pykobjê and Krĩkati to the region of Barra do Corda – which would complete the removal of the indigenous populations from the southern part of Maranhão, finalizing a process of colonization begun ninety years earlier.

The historic documentation on this transference is significant: in his report “Presented to the Inspectorate of the Indian Protection Service in the States of Pará and Maranhão, on the transference of the ‘Caracatys’ and ‘Gaviões’ Indians,” Marcelino Miranda tells us the following:

I present your good sirs with a report of the facts concerning the transference of the Indians of Grajahú to Barra do Corda, which you entrusted me to carry out following the threats against the same made by farmers living in the area and at the demand of the State government, which declared that if they were not removed, it would order their removal. The Indians concerned are the Gaviões and Caracatys of ‘São Félix’ and ‘Recurso’ villages located 105 km from the town and 24 km from each other.

Given the poor situation in which the Caracatys from the ‘Canto da Aldeia’ find themselves in the municipality of Imperatriz, I realized that the transference would have to include the entire tribe ... This village is situated 66 km from Grajahú.

... I do not know which of their enemies had the sinister idea of spreading the false rumour that the forest natives were preparing to attack Grajahú and put an end to Barra do Corda ... At the same time they instil in them (the Indians) the idea that the Inspectorate would have them killed...

The day after (July 2nd) my arrival (in the village of São Félix), I explained to the Indians the motives that had led me to those villages this time. But all of them refused to come to Barra do Corda. I then went to Recurso village, where the result was the same.

... So I decided to continue on to ‘Canto de Aldeia’ to see if I could bring the Caracatys (...) having arrived early morning on the 24th of the said month – I stayed overnight at the house of the farmer, Major Salustiano Gomes, half a league from the village in question, arriving precisely when night was falling (...) leaving for the village on the following morning.

As the gossip had arrived there too, I went to meet the Indians camped half a league from the village. They then headed to the latter in my company where I tried to convince them that they should come to Barra do Corda and I placated them as well as I could (...) The Indians who refused to come immediately fled to a nearby tract of forest, meaning that I was only able to bring seven men and five women.”

Mr Miranda adds that even after having a swidden cleared for them at Barra do Corda and given them food, clothing and tools, the Krĩkati

wanted to head to the village and I quickly realized that if I detained them any longer here, they would flee for good. I therefore gave them enough food for their journey and let them leave satisfied, instructed to invite their comrades to come. My plan was to fetch them last September, but a Mr Manduca Milhomem, living at ‘Campo Alegre’ some two leagues distant from the village, led them under various pretences to where he lives, writing afterwards to say not to fetch them, nor would he bring them while, according to him, they owed 500,000 réis in goods that he had sold to them ... I realized that he had told the Indians to flee and that I would be wasting time and money. Hence I decided to contact the State President, which I did by letter, for help them against this pernicious intruder ... and my son-in-law Antonio Miranda wrote to Manduca instructing him to allow the Indians to return to the village or else be held responsible under civil and criminal law (...)”.

The following is the Krĩkati’s own account of the same events:

When we were living at Canto da Aldeia, we would sometimes kill a few cows belonging to the cupen. At first the cupen gave a few heads of cattle to keep us happy. Afterwards the oldest people died and their children stopped following the customs, but we had got the taste for beef and once in a while we would kill cattle. But then the cupen contacted Marcelino Miranda who was the representative of the SPI in Barra do Corda. Marcelino came and stayed as a guest with the cupen. Our people were singing, it was the finale to the wyty festival of Neuto, my elder brother, who is right here.

We had made an encampment at a place called Akrãré, close to the village. Marcelino arrived there with other cupen. We were afraid and ran into the forest. Finally Mariano, my father and the ‘owner’ of the festival, confronted Marcelino.

Marcelino said that we had to abandon the village since he had orders from the government and the SPI already had an area of land allocated for us in Barra do Corda. We were forced to go: we were circled by police who led us, like cattle, to Rodeador (the tract of land acquired by the SPI to accommodate the Gaviões and Krĩkati); but people fell by the wayside here and there and when the group arrived there were just fifteen Indians and they ended up clearing a swidden there before returning to the village” (Francisco Milhomem Krĩkati).

This plan makes explicit the practice typically used by cattle ranchers to occupy the mid-south of Maranhão: offer a few heads of cattle to the village chief as payment for occupying the pastures within the indigenous territories.

From ‘leasers’ to ‘owners’

However, as the Indians themselves claim, with the passing of the years this relation altered: from ‘leasers’ of the land (from the Indians), the descendants of these small farms began to consider themselves ‘owners’ of land (of the Indians), interpreting the payment of the lease that their parents or grandparents had given to the Indians as the purchase of a right to possession: it was on the basis of this ‘legitimization’ that they would later justify the massacres for the killing of their cattle.

This inversion of the relation ended up leading some Timbira groups, like the Krahô and Ramcôcamekra, to messianic movements. These events were intended to revive the terms of the past alliance – the peaceful coexistence – with the first farmers, marked by the ‘donation’ of heads of cattle. From the moment when these ‘donations’ started to diminish, until ceasing completely as a practice, the Indians, reaffirming the right to their territories, once again started killing the cattle of the cupen. The objective of the messianic ritual was to obtain through magical means the donation of large herds of cattle and all the goods of the cupen – which in the eyes of the Indians legitimized their action (the constant killing of cattle) since all these herds would in fact be the property of the Indians when Aukê, the ‘messiah,’ arrived.

The history of the Timbira groups over the course of the twentieth century is largely based, therefore, on the dispute for territory involving the killing of cattle, which culminates in the emergence of two messianic movements among the Krahô in 1951 and the Ramcôcamekra in 1963; and the massacres of the Krahô (1940), Ramcôcamekra (1963) and Kênkatêgê (1913) and/or threats that justified the ‘protective’ action of the SPI. However in attempting to transfer the Pykopjê and Krĩkati in 1930 and transferring the Ramcôcamekra-Canela (after the massacre), the SPI’s actions in fact ceded to the pressure of local interests.

It was due to this attempt at removal that the Krĩkati went through a period of almost total disintegration, to the point that Nimuendajú considered them extinct as an organized group; when he visited them in 1929, their survivors were “dispersing in every direction.” However that same year Nimuendajú signalled the presence of many Krĩkati among their Pykopjê neighbours in São Felix village, who had arrived over previous years, and the survivors of an unidentified Timbira group (Côtugrecatêjê) in the village of Recurso (ibid: 19). By emphasizing the extinction of the Krĩkati,

“Nimuendajú leads us to think that both groups (Pykopjê and Krĩkati) had amalgamated with other already extinct groups, thereby becoming a single group known under the name of the host group – the Pykopjê” (Barata 1981: 40).

This ‘amalgamation’ is practically a fact for the SPI, as we can observe in the report by Dr. Marcelino Miranda when he extends his orders for the Pykopjê villages (São Félix and Recurso) to the Krĩkati villages (Canto da Aldeia) with the explanation that “the relocation should encompass the entire tribe...”

However the Krĩkati reorganized themselves again as an autonomous group. They say that the people who “dropped by the wayside” ended up forming the village called ‘Estraira’ on the shore of the Traíra stream (an affluent of the Arraia) where they stayed until the end of the wyty festival (begun at the time of Marcelino Miranda’s arrival).

From this village a large number of families left to found the village of Macaúba “close to a cave in a really ugly place” and from there left to build Taboquinha village, “in a clean and beautiful spot.” This village must have been formed in 1936-1937 (Newton 1971: 27).

Four households (those of Benjamim, Marcelino, Bestolo and Mariano) had stayed in the village of Estraíra before later joining the rest of the group in Taboquinha village.

The Krĩkati recall that Taboquinha village was large and at this time food was abundant . But “it was the period when there were many severe epidemics, we bled from the mouth and began to die, people died quickly; we began to disperse again, there was a lot of gossip and a lot of sorcery; until finally they killed the sorcerer.”

But by then the people had already dispersed: one group of three to four families, “the people of the late Dominguinho,” went to found a village in a place called ‘Boi de Carro.’ Meanwhile the group of the late Agostinho built a village in a place called Piquizeiro. Later this group relocated to Baixa Funda, founding a new village there. The rest of the people who had formed the village of Taboquinha divided with one part going to found the village of Sucupira and the other forming a village on the Estraíra site again. The Estraíra village split shortly after with some families returning to the São Gregório River while most ended up going to form ‘Canto Grande’ village. Later the two groups merged again with the São Gregório group joining ‘Canto Grande’ village.

During this period the people of Sucupira village (caused by the split in Taboquinha village) migrated to the shores of the São José River, founding the old São José village, next to the site of the present-day village of this name. These were joined by some of the Krĩkati families living in Canto Grande, while the rest of the village moved to a site called Batéia.

Throughout this whole time, the people of the late Manduce continued to live ‘separate.’ From ‘Engenho Velho’ – a village visited by Nimuendajú in 1929 – this group went to live in Vão da Serra before later moving to a site called ‘Cabeceira das Cabras.’

In 1962, “because of the killing of cattle,” the farmers started to threaten the Krĩkati again, demanding that the mayor of Montes Altos, Jocino Gomes, take radical measures against the Indians. The mayor therefore called a meeting in the local council attended by representatives from all the Krĩkati villages existing at the time (Baixa Funda, Cabeceira das Cabras, Batéia and São José) and the farmers. This meeting led to the establishment of an agreement in which they Indians would receive a head of cattle to be consumed by the community in order for them to cease killing the pigs and cattle owned by the farmers.

The mayor chose two Indians who present on the occasion and spoke Portuguese well, Urbano and Francisco, to supervise compliance with the agreement. The mayor also counselled that all the Krĩkati should live together in a single village, which would facilitate the deal with the council (which signalled the possibility of some kind of assistance). In the context of this ‘cooperation,’ Friar Aristides, an Italian missionary who had just arrived at Montes Altos, would start a school in São José village with the agreement that all the Krĩkati children would study there.

Father Aristides’s school, whose teacher was another Italian missionary, Friar Antônio, was the main mechanism used by the regional politicians for the Krĩkati to cease inhabiting various parts of their territory simultaneously. Undoubtedly the sheer number of small villages had been hindering full occupation of sections of the Krĩkati territory by neighbouring farmers.

According to information contained in a report by anthropologist Delvair Montagner (FUNAI 1980: 55), the transference from Batéia village was carried out in October 1978, according to the records in the Post’s archives. However when the anthropologist was among the Krĩkati in 1979, she noted that there were still eleven people living in this village who had refused to reside in São José.

In 1979 the Krĩkati still inhabited three distant points of their territory: along the São José river (São José river); in the basin of the Bom Vivendo river (Batéia village); and on the Buenos Aires river (Areia village). From 1980 onwards the Krĩkati were all united in a single village, São José.

‘Areia’ village is made up of extended Guajajara families who live in the Krĩkati territory in the region of the Serra do Cipó uplands (in the far southeast) and with whom the Krĩkati intermarry. The Krĩkati consider them ‘additions’; in fact they are the only additional population who are loyal to them today. In the region of the Arraia river (in the ‘Green Forest’), on the southwest border, there still resides a single nuclear family.

Way of Life

For the Timbira time is seen as a sequence of summer (amcró) and winter (ta’ti), or more precisely, the dry season (spanning roughly from April to September) and the rainy season (roughly October to March). These two seasons regulate the two ceremonial periods of social life and the productive activities as a whole. Most of the rites linked to the annual cycle are concentrated in the rainy season, while the dry season is reserved for one of the rites linked to initiation.

The Krĩkati festivals (amji kin, literally: ‘to be joyful’), like those of the other Timbira peoples, relate to the annual cycle (festivals for maize, sweet potato, change of season), the initiation of young people, the regulation of kinship and interpersonal relations, using the relations between animals as a paradigm (such as the fish festival, the tayra festival, the mask festivals), the festivals relating to assuming or handing over the role of wyty (a boy or girl ritually associated with individuals of the opposite sex in the village) or the festivals and small ceremonies relating to the individual’s life cycle (the end of the couple’s reclusion after the birth of children, rites to reintroduce someone who has been away from the conviviality of the village for a long time due to illness or mourning). In these latter two cases (wyty and the life cycle), the responsibility for providing food and goods to the village belongs to the house of origin of the man or woman involved.

These festivals demand an abundant distribution of food and today some of them remain in a ‘latent’ period for several months until the village promoting the festival can provide the food and other items needed for its conclusion. As well as food, beads and cloth are needed to offer to participants from other villages.

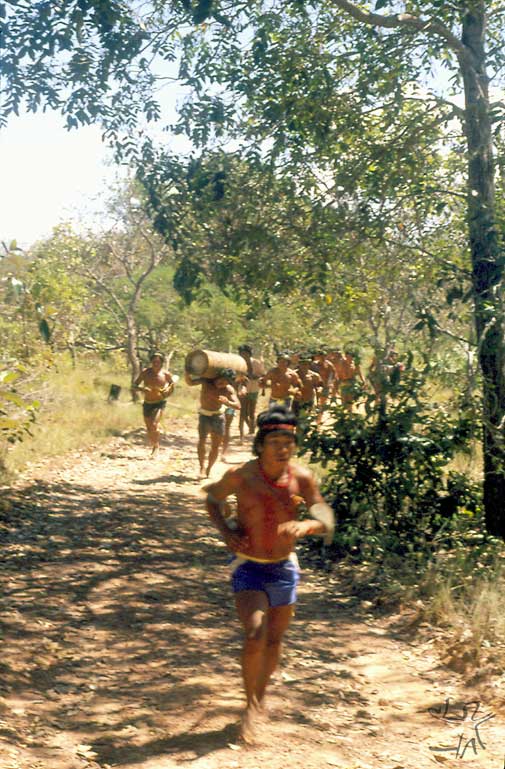

Each festival is marked by the name of a specific log race and specific songs – which leads to the conclusion that without a ‘singer’ (incrercatê) who knows the songs, the particular ritual cannot be held. Villages in this situation solve the problem by ‘hiring’ a singer from another village from the group itself of another Timbira village.

Hence the festivals epitomize the solidarity needed for convivial existence in the villages and represent moments that emphasize rules of behaviour. The amjkin, as well as providing a moment of ‘joy’ and relaxation (moments when young people can meet women from outside, while married men and women can engage in extramatrimonial sexual relations), are fundamental to actualizing the sociocultural structure and to maintaining the equilibrium of internal relations.

The ‘festivals ’therefore almost entirely fill the annual calendar of the villages: during any part of the year, a village is always preparing or performing a festival or waiting for the conditions to complete another.

For more information on the way of life and social organization of this people, visit the Timbira entry

Sources of information

- BARATA, Maria Helena. A antropóloga entre facções políticas indigenistas : um drama do contato interétnico. Belém : MPEG, 1993. 140 p. (Coleção Eduardo Galvão)

- COELHO, Elizabeth Maria Beserra. A política indigenista oficial na dinâmica da disputa pela terra : o caso da demarcação da terra Krikati. In: BARREIRA, Irlys; VIEIRA, Sulamita (Orgs.). Cultura e política : tecidos do cotidiano brasileiro. Fortaleza : UFCE, 1998. p. 51-75. (Percursos, 2)

- CORREA, Katia Nubia Ferreira. Muita terra para pouco índio? O processo de demarcação da Terra Indígena Krikati. São Luis : UFMA, 2000. 208 p.

- LADEIRA, Maria Elisa. Krikati : um longo processo para o reconhecimento de suas terras. In: RICARDO, Carlos Alberto (Ed.). Povos Indígenas no Brasil : 1987/88/89/90. São Paulo : Cedi, 1991. p. 491-2. (Aconteceu Especial, 18)

; AZANHA, Gilberto. Os “Timbira atuais” e a disputa territorial. In: RICARDO, Carlos Alberto (Ed.). Povos Indígenas no Brasil : 1991/1995. São Paulo : Instituto Socioambiental, 1996. p. 637-41.

- LAVE, Jean Elizabeth Carter. Social taxonomy among the Krikati (Ge) of Central Brazil. Cambridge : Harvard University, 1967. 384 p. (Tese de Doutorado)

- NEWTON, Dolores. Social and historical dimensions of Timbira material culture. Cambridge : Harvard University, 1971. 342 p. (Tese de Doutorado)